27 Apr Rock and roll and ramen: Lessons in appropriation vs appreciation

My friends (and anyone who follows my social media “food porn” photos) know that I’m a snob about Japanese food. I have strong opinions on the best tonkatsu fried pork cutlets, real vs. fake sushi and Japanese restaurants staffed by non-Japanese who can’t pronounce menu items correctly. And, because I love ramen, I hate bad ramen – and in Denver bad ramen is much more common than the good stuff.

That doesn’t mean I won’t pick up a tray of sushi at a supermarket, or dine at Japanese restaurants that aren’t owned or run by Japanese. I still enjoy the occasional family meal at Benihana, even though the steakhouse chain seems to be staffed mostly by Latino chefs entertaining diners at their teppanyaki grills. And I’m not offended by fusion dishes like sushirritos, large sushi presented burrito-style with nori instead of tortillas.

Let’s face it, one of the most wonderful example of cultural mashups – the Hawaii-born Spam Musubi – is an example of foodie fusion at its best. And Japanese curry, which is completely different from Indian or Thai curry, is a fusion dish that’s a result of colonialism spreading the spice.

But I am offended by lousy Japanese cuisine presented as authentic, whether by Japanese or non-Japanese restaurateurs, that seems like a calculated marketing move to jump on a popular bandwagon. Tokyo Joe’s is one Colorado-based chain that was calculatingly designed to fill a culinary niche: fast-casual Japanese-inspired food that was healthier than a Panda Express Orange Chicken. The thought that people who eat at Tokyo Joe’s may think that’s “real” Japanese food, drives me crazy.

I’ve often griped about authenticity and appropriation in Japanese food and culture, from whitewashing Japanese characters with white actors and inaccurate portrayals of Japan in Hollywood and using that old-school offensive typeface “wonton,” to disrespecting Japanese culture with poor imitations of its cuisine.

But my college roommate Joe, who has for decades served to keep my head from blowing up too big, pointed out after one of my Facebook rants about authenticity, that rock and roll has its roots in cultural appropriation.

That made me think. And he’s right. Rock and roll music evolved out of a fusion of African American music (gospel, blues and jazz) with white southern country and folk strains. Joe and I were huge music fans during school and both worked at the campus radio station. Joe also taught me how to play guitar. In large part because of our diverse musical immersion I was a music critic for many years after college.

The primordial musical stew that cooked up Elvis Presley and other early rock pioneers was spiced with black artists who voiced the experience of the church and plantation, urban migration, racism and heartbreak. Some of the major labels’ early attempts to cash in on the rising popularity of black music with the young post-war generation (soon to be called baby boomers) were tepid whitewashed versions of black music, re-recorded by creepy white crooners like Pat Boone. But young people who knew better preferred the real deal, embodied in exciting, sexy, authentic performers like Chuck Berry and Little Richard.

White performers that caught the younger fans’ attention had the passion for black music, like Bill Haley and the Comets, Buddy Holly (who also wrote his own songs, which was revolutionary in itself) and of course King Elvis, who was mistaken for black when his first single went out over the radio waves.

But the competing processes of appreciation and appropriation – the real and the commercially invented (like Tokyo Joe’s in our Japanese food example) – eventually converged into assimilation. Black music became commercially popular in the form of Motown, soul music and the R&B of the 1960s and ‘70s and white rock and roll absorbed its original influences and then invented its own distinct styles, with the Beatles as the most obvious example.

So is Japanese food undergoing its own period of assimilation after appreciation and appropriation?

I’m still in the appreciation camp. I look for the authentic experience and try to educate people about why I love the real thing. But I know that change is inevitable, and that food culture by its nature absorbs, assimilates and evolves all the time. So maybe out of the fakery will come new forms of Japanese-inspired cuisine. And maybe I’ll like it. Spam Musubi is a yummy example.

Spam Musubi, a Hawaiian-born mashup of sushi and US military food.

For now, though, instead of the aforementioned Tokyo Joe’s (the name even bugs me), if you’re in Denver and you want to try better fast-Casual Japanese, visit Kokoro, a restaurant with two locations that serves beef and chicken bowls and other dishes. Kokoro is owned by a Japanese man who came to the area to manage Denver area locations for the Japanese chain Yoshinoya Beef Bowl in the 1970s, and took over his restaurant when the chain pulled out of the state.

Meh sushi is rampant in area restaurants, including Tokyo Joe’s. Some Chinese and Korean restaurants have added sushi to their menu (and some have just decided to call themselves “Asian Fusion” and sell everything from Chinese and Thai to sushi and teriyaki), and unskilled “chefs” sloppily roll up rice and ingredients without regard for the correct texture or slight vinegary flavor of the rice.

I’ve long since accepted the idea of huge “handrolls” at non-traditional sushi bars with stuff thrown into a cone of nori seaweed. And I’ve gotten used to the idea of a California Roll with rice on the outside, which can now be found even in Japan (it’s American-style sushi). As a side note, my mom looked aghast the first time she saw a California Roll, and said, incredulously, that it was “inchiki sushi,” or fake sushi, because putting rice on the outside of a roll seemed like such a stupid idea.

Here’s what I hate about lousy sushi: Fishy ingredients (fresh sashimi isn’t fishy), overcooked or undercooked rice, no flavoring and sloppy, loosely rolled pieces. I don’t expect the top level of artistry that’s documented in the film “Jiro Dreams of Sushi,” about the Tokyo restaurant where a lunch costs $300 and seats need to be reserved months in advance.

Good, fresh, real sushi!

But I’m not an absolutist. I can even put up with cheap supermarket sushi when I have a comfort food craving for, say, an inari sushi. When a restaurant serves bad sushi for good money and tricks diners into thinking they’re serving the real stuff, that’s when I get mad.

Ramen is a passion of mine, so I welcomed the slow arrival of ramen to the Denver area, years after the noodle invasion had taken hold in cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York. I grew up with ramen in Tokyo where Shoyu Ramen reigns, and have had amazing Miso Ramen in Sapporo, and even more amazing Tonkotsu Ramen in Kumamoto (Kyushu is the home of tonkotsu ramen). I also slurped the best of the country at the Shin-Yokohama Raumen Museum, a totally cool place dedicated to ramen culture, where the top shops in the country serve half-bowl samplers for cheap.

So I’ve been excited that ramen is catching on in the Denver area.

But out of the 30 or so places that now claim to serve ramen, more than 20 serve some combination of ramen noodles in a soup with haphazard toppings that may or may not be authentic. A few Japanese restaurants swerve the real thing in OK quality (the aforementioned Kokoro serves a ramen that’ll do in a pinch, and Sakura House in Sakura Square has a bunch of ramen styles on its menu that are better than average).

Some serve pretty decent quality ramen: Sushi Den and Ototo, its brother restaurant, serve a decent bowl; Osaka Ramen is very good – better when owner Jeff Osaka is in the house; I’ve had good and bad at Katsu Ramen.

But too many are over-rated hipster joints like Daikokuya, a mysteriously popular place in LA’s Little Tokyo that always has people waiting in line for no good reason. Uncle in the hipster haven of Denver’s Highlands neighborhood is a similar such pretender. Don’t get fooled by the people who are willing to wait an hour to get in. They just don’t know better.

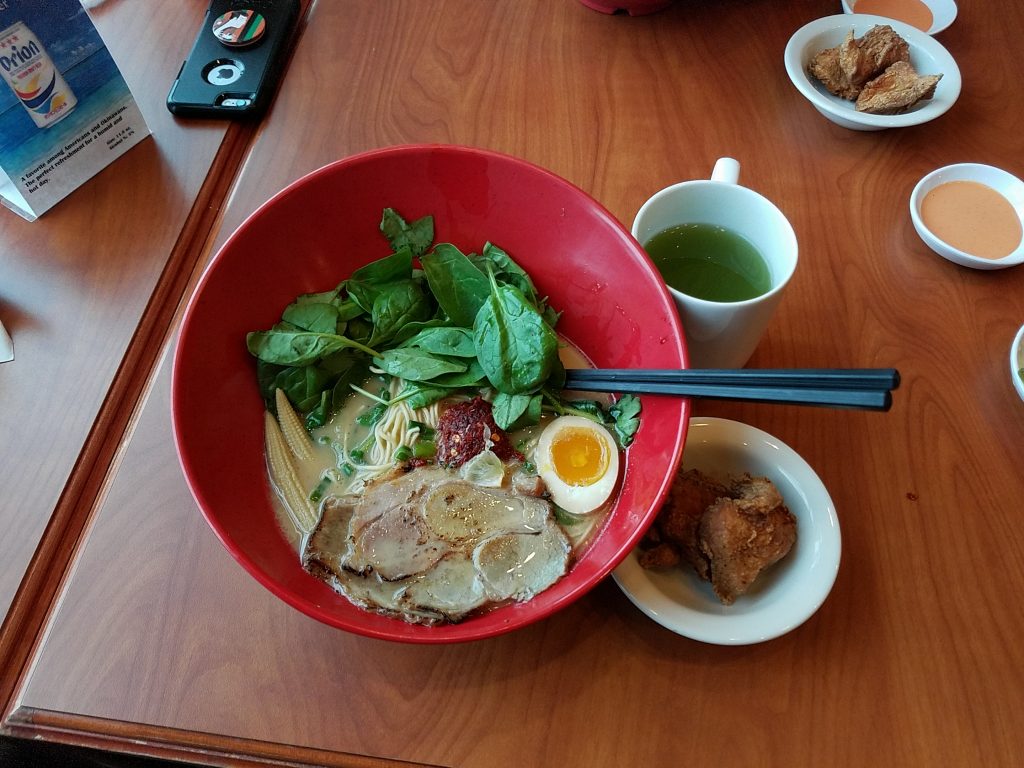

The two best ramen shops in the Denver area are Tokio and Rocky Mountain Ramen (photo at top of page).

At Tokio in the shadow of Coors Field, you can get ramen in a list of interesting variations (speaking of fusion, including a Cremoso Diablo, a spicy cheesy soup) including of course, a very good tonkotsu, and the best noodles in the area. Owner Miki Hashimoto, who sold his popular Denver sushi restaurant to study ramen craft in Japan then came back to town, fine-tunes his noodles from the nationally renowned supplier Sun Noodles to his precise requirements and they’re a pleasure to slurp and bite into. His soups are always top-notch too. Tokio also has a fine sushi bar and a unique Bincyotan Grill, which uses special Japanese charcoal to cook skewered meats and vegetables.

Rocky Mountain Ramen, north of Denver and east of Boulder is a drive for hipsters but not bad for northwest suburbanites like me, ans is tucked away next to a Starbucks in an unassuming strip mall in Erie. Its owner Mitsu Wada, who’s from Yokohama, and his chef Masa Nozaki from Okayama, are perfectionists and their attention to detail pays off. Their tonkotsu soup is the best in the area, a pleasure to drink up every drop in the bowl. I never leave any – it’s like drinking meat. Rocky Mountain Ramen simmers hand-selected pork bones for up to 20 hours to get it right.

Many places that serve “tonkotsu” ramen just use soup mixes that approximate the taste but you can tell from the lack of depth, umami and collagen. At Rocky Mountain Ramen, however, there’s no corner-cutting; even their teriyaki chicken is made with house-made sauce, no gloppy fake teriyaki sauce out of a bottle here.

One thing I’ve learned from my love for ramen: The history of ramen in Japan is itself a prime example of appreciation and appropriation and ultimately, assimilation.

Ramen began in Japan as “Shina Soba” or Chinese noodles, a low-class street food sold by Chinese vendors for Chinese laborers in Yokohama in the late 1800s. But Japanese caught on that it was hearty, cheap comfort food. After WWII, ramen became a staple, in part because the US forced Japan to buy surplus wheat from American farmers. But ramen became a cultural icon in Japan after instant ramen was invented in the 1950s, and Cup Noodles was invented (by the same company in the 1970s).

Real ramen continued to be served in restaurants and evolved as various regions created their own signature styles. Some added different ingredients, or used different soup bases, like miso, salt or even created a style that serves noodles and toppings separate from a cup of concentrated soup for diners to dip.

In Japan, ramen variants are always being invented and new twists are always bring tried. So I shouldn’t cringe when someone tries something different with ramen here (like the broccoli that showed up in a bowl in one place).

Like with other Japanese food, it’s the fake stuff, with packaged soup and packaged noodles sold as authentic, that makes me mad. In the end, I shouldn’t mind the fusion or even the phony stuff from time to time. This is America, not Japan, and even in Japan, variations are always being added to the traditional foundations.

When I’m hankering for the real deal, though, it’s worth the extra step – and miles – to seek out the authentic Japanese food. Crank up Little Richard over Pat Boone, anytime!

An earlier version of this post was published on Discover Nikkei.