28 Aug Book reviews: End-of-summer reads about JAs and Japan

When the Japanese Canadian newspaper Nikkei Voice asked me to write about my favorite recent books related to Japan, I realized that I’ve read some books in the past year that I never got around to writing about, and was also finishing an innovative new book, or to be precise, a new ebook.

In any case, I tend to read many more non-fiction books by and about Japan and Japanese Americans than I do any fiction titles, so it’s sort of surprising to me that two of these books are flat-out fiction (albeit based on the author’s childhood for “Kazuo’s World”) and that another is fiction manga based on history and another is history told through a fictionalized manga lens.

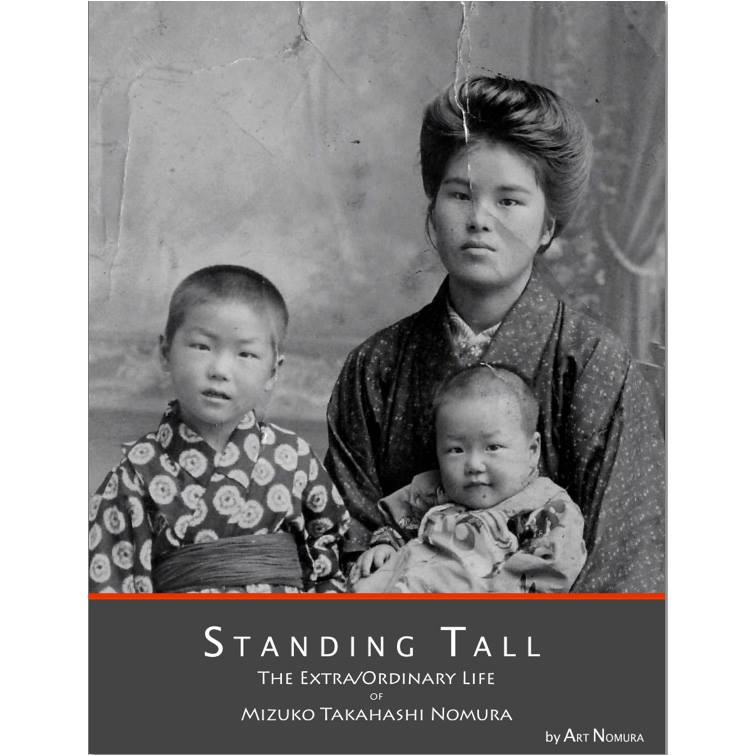

Standing Tall: The Extra/Ordinary Life of Mizuko Takahashi Nomura

The most recent book I’ve read is “Standing Tall: The Extra/Ordinary Life of Mizuko Takahashi Nomura,” by Sansei artist, filmmaker and film professor Art Nomura. It’s a biography of Nomura’s grandmother, who immigrated to the U.S. in the early 1900s, made as an interactive iBook for iPads, iPhones and Macs. The family history is well written but what makes it special is the chockfull of extra information, side stories, games, clickable images and links to other resources that Nomura includes. The book is a fascinating, well-researched read — though Nomura admits he’s made up conversations and details of his grandmother’s early days in Japan, it’s as detailed and factual as possible. It’s certainly a great look at one Issei woman’s epic life, and the experience is made that much richer with all the extra information Nomura adds, utilizing the iBook format to its fullest. The downside of being on the cutting edge, of course, is that unless you have a Mac computer, an iPad or an iPhone, you won’t be able to read this delightful loving biography.

The most recent book I’ve read is “Standing Tall: The Extra/Ordinary Life of Mizuko Takahashi Nomura,” by Sansei artist, filmmaker and film professor Art Nomura. It’s a biography of Nomura’s grandmother, who immigrated to the U.S. in the early 1900s, made as an interactive iBook for iPads, iPhones and Macs. The family history is well written but what makes it special is the chockfull of extra information, side stories, games, clickable images and links to other resources that Nomura includes. The book is a fascinating, well-researched read — though Nomura admits he’s made up conversations and details of his grandmother’s early days in Japan, it’s as detailed and factual as possible. It’s certainly a great look at one Issei woman’s epic life, and the experience is made that much richer with all the extra information Nomura adds, utilizing the iBook format to its fullest. The downside of being on the cutting edge, of course, is that unless you have a Mac computer, an iPad or an iPhone, you won’t be able to read this delightful loving biography.

Still, I find myself reading more and more on my tablets or even smartphone, but none of my other ebooks are native to the digital format. Reading is evolving like everything else in our digitally-connected society, and people like Nomura are taking full advantage of the new technology. Kudos to him!

The following four books are all dead-tree books, though. Graphic novels especially, just don’t translate to digital page:

Jet Black and the Ninja Wind (Tuttle)

“Jet Black and the Ninja Wind” is an action novel by the Tokyo-based couple of Leza Lowitz and Shogo Oketani that’s aimed at Young Adult readers, but I found it perfectly entertaining as an adult (no snarky comments about my juvenile mind). It’s about a young mixed-race high school student who finds herself embroiled in a mysterious search for her family’s ninja history when her mother is killed. The authors get the teenaged angst just right on this side of the Pacific, and the cultural points and details of life in Japan are spot on. The story is exciting in a 007-meets-the ninja-movies-of-our-childhoods way, and builds to a climax back in the US that would play well as a Hollywood action blockbuster. It’s hard to tell how much of the writing is Lowitz and how much is her husband Oketani, but the American part of the story believably evokes the life of an American teenager and the stuff that takes place in Japan is set in a believable culture too. There has been talk of film rights — this would definitely make a cool movie. I’m looking forward to sequels.

“Jet Black and the Ninja Wind” is an action novel by the Tokyo-based couple of Leza Lowitz and Shogo Oketani that’s aimed at Young Adult readers, but I found it perfectly entertaining as an adult (no snarky comments about my juvenile mind). It’s about a young mixed-race high school student who finds herself embroiled in a mysterious search for her family’s ninja history when her mother is killed. The authors get the teenaged angst just right on this side of the Pacific, and the cultural points and details of life in Japan are spot on. The story is exciting in a 007-meets-the ninja-movies-of-our-childhoods way, and builds to a climax back in the US that would play well as a Hollywood action blockbuster. It’s hard to tell how much of the writing is Lowitz and how much is her husband Oketani, but the American part of the story believably evokes the life of an American teenager and the stuff that takes place in Japan is set in a believable culture too. There has been talk of film rights — this would definitely make a cool movie. I’m looking forward to sequels.

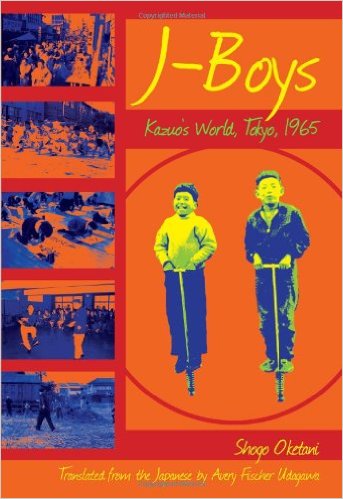

J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965 (Stone Bridge Press)

I was drawn to Oketani’s short novel, “J-Boys, Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965,” because I was born in 1957 in Tokyo, and moved to the US in 1966 when I was 8. Kazuo is a 9-year-old boy in 1965 Tokyo, and is based on the author’s own childhood. Oketani follows his prosaic but fondly remembered year in school, being influenced by American rock and roll, and hanging out with friends. He captures the feel of Japan as it flexed its industrial muscles a year after its coming-out party of the Tokyo Olympics, becoming an international player. The book is like a snapshot of its time and place, and a fun time travel trip for me to a Japan in the days before McDonald’s and KFC arrived there. The photos of Tokyo from that era add to the book’s evocative spell.

I was drawn to Oketani’s short novel, “J-Boys, Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965,” because I was born in 1957 in Tokyo, and moved to the US in 1966 when I was 8. Kazuo is a 9-year-old boy in 1965 Tokyo, and is based on the author’s own childhood. Oketani follows his prosaic but fondly remembered year in school, being influenced by American rock and roll, and hanging out with friends. He captures the feel of Japan as it flexed its industrial muscles a year after its coming-out party of the Tokyo Olympics, becoming an international player. The book is like a snapshot of its time and place, and a fun time travel trip for me to a Japan in the days before McDonald’s and KFC arrived there. The photos of Tokyo from that era add to the book’s evocative spell.

Secrets of the Ninja (Blue Snake Books)

Who doesn’t like ninja? More than even samurai, these special warriors of Japanese history are alluring to westerners. Sean Michael Wilson is a Scottish writer writing manga in Japan; Akiko Shimojima is a Tokyo based artist, and the two have teamed up to create “Secrets of the Ninja,” a manga about the roots of shinobi, the ninja arts. The story is about a young man’s coming-of-age as he trains to become a ninja. The training is based on the writing of Hattori Hanzo, a famous real-life ninja, so this is fiction, but based on historical writing. The text is terse and dynamic, and the artwork is well-drawn and engaging. There’s a supplement at the end by Antony Cummins that includes historical context and entries on many of the tools of the ninja trade.

Who doesn’t like ninja? More than even samurai, these special warriors of Japanese history are alluring to westerners. Sean Michael Wilson is a Scottish writer writing manga in Japan; Akiko Shimojima is a Tokyo based artist, and the two have teamed up to create “Secrets of the Ninja,” a manga about the roots of shinobi, the ninja arts. The story is about a young man’s coming-of-age as he trains to become a ninja. The training is based on the writing of Hattori Hanzo, a famous real-life ninja, so this is fiction, but based on historical writing. The text is terse and dynamic, and the artwork is well-drawn and engaging. There’s a supplement at the end by Antony Cummins that includes historical context and entries on many of the tools of the ninja trade.

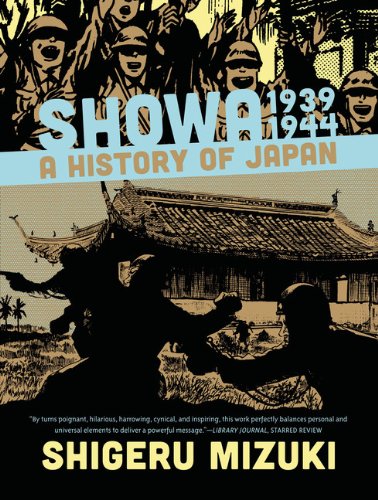

Showa: A History of Japan (Drawn & Quarterly)

“Showa” is a gargantuan four-volume history of modern Japan presented as a manga by legendary artist Shigeru Mizuki, translated by Zack Davisson. The series are broken down by eras of Japan’s Showa Emperor, the Japanese name for the man we remember as Hirohito. The volumes cover 1926-1939 when Hirohito takes over the country from his ill and feebled father Emperor Taisho, 1939-1944, 1944-1953 and 1953-1989 when Hirohito died. Originally published in Japan, it’s been published stateside over the past couple of years. Mizuki follows the country’s epic journey from an emerging nation to a war-mongering world power to the humbling postwar Occupation years and its resurrection as a world power. Some Japanese objected to Mizuki’s anti-war perspective but it’s a clear-eyed view of life during those tumultuous decades from a man who lived through it. The books are an astounding display of drawing brilliance, combining photorealism with cartoony imagery, and bringing characters to life as we follow the better part of a century of Japan’s history. This ain’t no comic book — it has humorous elements to it but much of the volumes relay a serious and thought-provoking message about war and peace. It’s definitely worth a read!

“Showa” is a gargantuan four-volume history of modern Japan presented as a manga by legendary artist Shigeru Mizuki, translated by Zack Davisson. The series are broken down by eras of Japan’s Showa Emperor, the Japanese name for the man we remember as Hirohito. The volumes cover 1926-1939 when Hirohito takes over the country from his ill and feebled father Emperor Taisho, 1939-1944, 1944-1953 and 1953-1989 when Hirohito died. Originally published in Japan, it’s been published stateside over the past couple of years. Mizuki follows the country’s epic journey from an emerging nation to a war-mongering world power to the humbling postwar Occupation years and its resurrection as a world power. Some Japanese objected to Mizuki’s anti-war perspective but it’s a clear-eyed view of life during those tumultuous decades from a man who lived through it. The books are an astounding display of drawing brilliance, combining photorealism with cartoony imagery, and bringing characters to life as we follow the better part of a century of Japan’s history. This ain’t no comic book — it has humorous elements to it but much of the volumes relay a serious and thought-provoking message about war and peace. It’s definitely worth a read!

NOTE: An edited version of this post originally ran in Nikkei Voice, the national Japanese Canadian newspaper of the Nikkei Research and Education Project of Ontario.