21 Jul Vincent Chin’s murder 35 years ago galvanized a pan-Asian movement

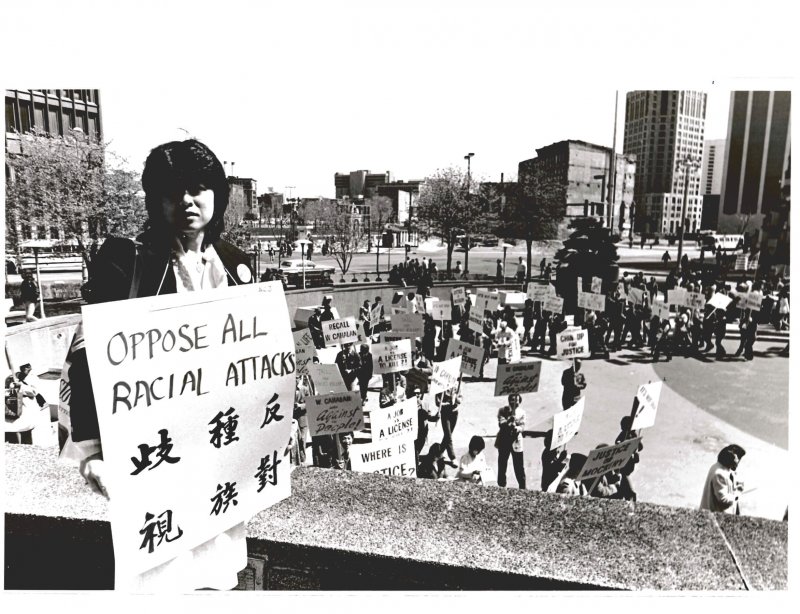

Vincent Chin rally in Detroit, 1983 (Photo by Victor Yang, China Times)

Vincent Chin rally in Detroit, 1983 (Photo by Victor Yang, China Times)

On the night of June 19, 1982, 27-year-old Vincent Chin was celebrating his bachelor’s party with friends in a Detroit strip club. He got into an altercation with two white men, and both groups were thrown out. The two men tracked down Chin with the help of a third man and brutally beat him with a baseball bat.

Their reason? They blamed the downturn of the Detroit auto industry on Japanese cars, which were at the time overtaking American models in popularity. They thought Chin was Japanese. He was Chinese American.

Vincent Chin was left in a coma and died four days later, on June 23 — a few days before his scheduled wedding. The two men from the club (one of them was the killer while the other held Chin) were charged with second-degree murder but the charge was reduced to manslaughter and neither served any jail time. They were ordered to three years probation and to pay $3,000 in fines.

A young Asian American journalist, Helen Zia reported on the murder, then led the efforts to bring federal civil rights charges against the men. In the end, the accused murderers settled a civil suit out of court. Ronald Ebens, the man who beat Chin, was ordered to pay $1.5 million, but Chin’s estate has never received any payment.

It was national news when it happened, but it’s faded from memory for most people.

Helen Zia (Photo by Jason Jem)

For the anniversary, Zia, who now lives in San Francisco, returned to Detroit for the commemoration of Vincent Chin’s death.

In an interview, Zia, who’s since written a book with Wen Ho Lee, the scientist at Los Alamos who was wrongfully accused of espionage for China, and served as executive editor of Ms. magazine from 1989-’92, is typically modest about the impact of “Asian American Dreams.”

When asked how she feels about the book being a gateway for a generation of young AAPIs’ social justice activism, she says softly, “I don’t think that’s for me to say. I feel like I was part of a generation of Asian Americans coming of age of our community.

“We were part of a group that had a critical mass of numbers and saw the voice we could have together,” she adds. “I was able to write about that and chronicle that.”

Chin’s murder was one spark for the community’s coalescing, but it wasn’t the sole inspiration for the book, she says. “It was definitely part of a whole feeling that I had, that our stories were not being told. The way I imagined it was that little balloons would pop up occasionally involving an Asian American then it would pop and disappear. We were blips. It was striking that we were not considered newsworthy at all, that we weren’t part of the community.”

“Vincent Chin was one of many stories and I saw it from the street level,” she says. “I had to tell it just to get it out myself, it was so distressing.”

Thanks in part to Zia’s efforts, there’s more awareness of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders has a bigger presence in the media today. “There are more Asian Americans in the news occasionally. We should be now — we’re approaching 6% of the American population. But much of the news looks at Asian Americans as invaders still, untrustworthy….”

Zia is back in Detroit this week to commemorate the 35th anniversary of Vincent Chin’s death.

She acknowledges that Chin’s legacy today is a wider awareness of hate crimes. “The case opened up civil rights law, broadened it to cover immigrants. I credit that debate and decision to lead to where we are now, with hate crimes laws. I can’t even count the number of organizations now that are watchdogs for hate crimes.”

“Vincent Chin was killed in a national climate of extreme rhetoric against Japanese or anyone who happened to look Japanese,” she notes. “But his death led to the expansion of the justice coalition to include Asian Americans. To say we are all human beings and deserve to be treated with full human dignity.”

(Note: This post was originally written for AARP’s Voices blog)