03 Sep What does celebrating Woodstock have to do with Asian Americans?

In a previous life during my long and winding journalism career, I was a rock critic. I was the music editor for Denver’s weekly newspaper, Westword. So when the Denver Press Club recently asked me to participate on a panel discussion for the 50th anniversary of the Woodstock music festival, I was eager to join in the fun.

I write a monthly column for Asian Avenue Magazine as a member of the Denver Asian American Pacific Islander Commission (DAAPIC), and the mag suggested I write about this panel for the September issue. What does a talk about a 50-year old music festival have to do with DAAPIC? Admittedly not much… except for me, since I’m a commissioner.

Here’s how being Asian American is part of this story:

I became a rock critic because I loved rock and pop and soul music when I was a kid. From the Beatles to the Stones to Motown and Aretha, and all the stars and one-hit wonders in between, I was glued to my radio. I was a fan, and an opinionated one at that, thanks to the emerging music press back then, primarily Rolling Stone magazine.

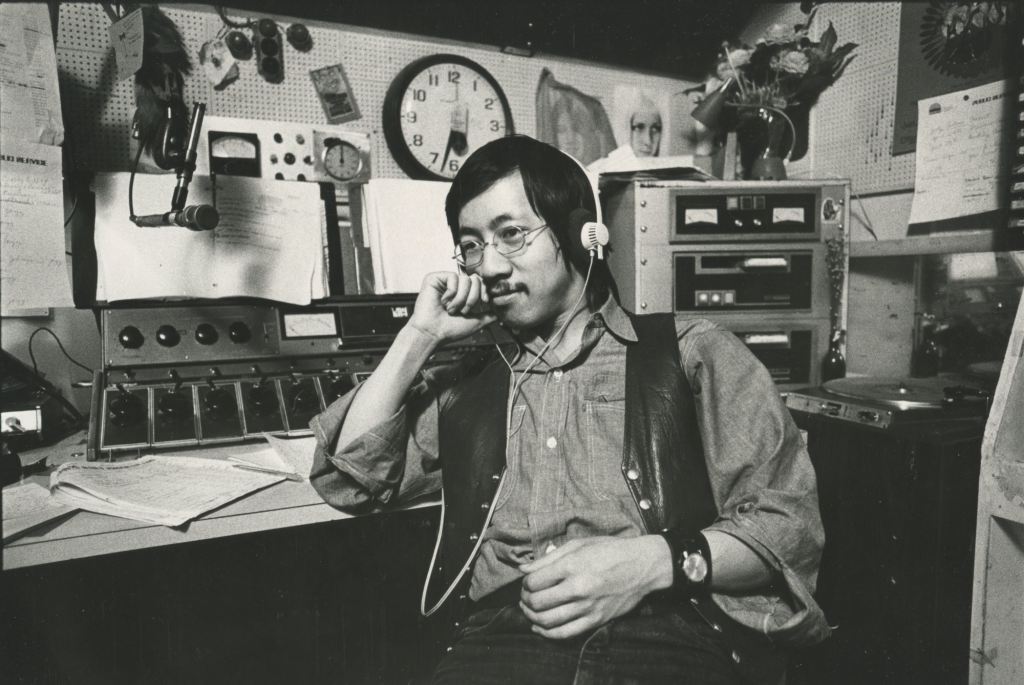

And in the early years of the magazine, I saw that one of the founding editors was Ben Fong-Torres. Somewhere I saw a photo and confirmed that he’s Asian. I found out years later when I read his excellent memoir, “The Rice Room,” that he is Chinese American whose family went to the Philippines and paid to add “Torres” to their name because it was legal for Filipinos to emigrate to the US but not Chinese. You might be familiar with the semi-autobiographical movie “Almost Famous,” about the young Cameron Crowe, who wrote for Rolling Stone in the 1970s. His editor in real life and depicted in the movie, was Ben Fong-Torres. Watch for “Like a Rolling Stone,” a documentary about Fong-Torres, which is coming out soon.

Anyway, the fact that a writer with an Asian face was one of my heroes, covering rock and roll in my favorite magazine was an inspiration to me. I began reviewing records for my high school newspaper (Alameda High School Paragon in Lakewood, Colorado – my first article was a review of the Doobie Brothers’ “Stampede” album!), and when I went off to art school in New York City, I began writing music for a college newspaper entertainment insert, which continued after college for the Colorado Daily in Boulder, then Westword.

I eventually even got to write some freelance pieces for Rolling Stone and other national music publications. And, I got to meet Ben Fong-Torres as an adult, and thank him for inspiring me.

That’s what DAAPIC is about. Nothing like this commission existed when I was a kid. But with our activities supporting the area’s Asian Pacific Islander Desi American community with arts grants or job fairs or policy guidance for the city, if we can inspire some young kid to find their passion and follow their dreams… well, that’s our goal. That is, unless the kid has tiger parents who are determined to have them grow up to be a doctor, lawyer or engineer. Luckily, I didn’t, or I never would have been able to go to New York and get a degree in painting.

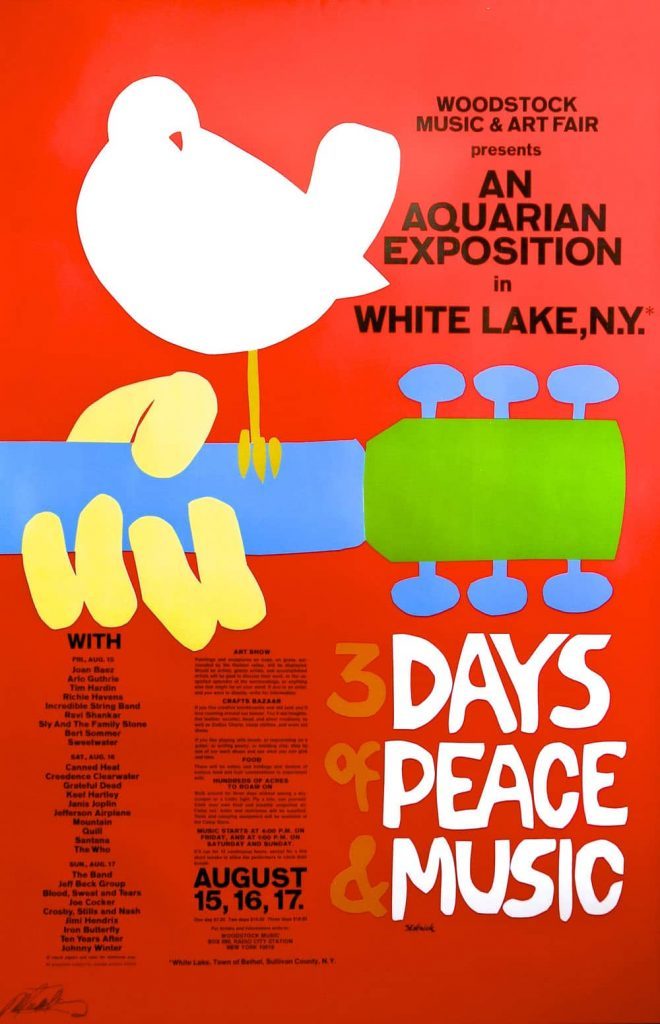

I haven’t written about music for years – except for covering Asian American artists, who seldom are covered by mainstream music media – but because of my ancient past, I was asked to be on the Woodstock panel. The music festival was held Aug. 15-18, 1969, in the town of Bethel, New York upstate from New York City. It took over the dairy farm pasture belonging to Max Yasgur, a nice, unsuspecting farmer who was probably as shocked as anyone when over 400,000 young people flooded his land to enjoy the weekend of music and art (and rain, and mud). There were so many people who converged on the concert that the state closed down the highway, and the festival organizers were forced make it a free event instead of trying to charge everybody.

Because it was such an important milestone for the baby boom generation, coming towards the end of the turbulent 1960s, Woodstock has become an iconic symbol of its times. It’s also become so well-known because it was filmed for a documentary, and the film was released less than a year later, in March, 1970. My friend Allen Shumway’s mom drove us to a theater in McLean, Virginia so we could see the film, which clocked in at over two hours. Subsequent versions of the documentary have been edited longer and longer, and the blu-ray disc has an insane amount of music that wasn’t in the original movie, including sets by Creedence Clearwater Revival and Grateful Dead.

I was just 11 years old when Woodstock was held, so of course I didn’t attend. I probably would have hated it anyway, because of the crowds and the mess. And, frankly, some of the lousy music from overrated acts like Alvin Lee and Ten Years after, and Canned Heat, whose set in the film was longer than it needed to be.

But there was great music from a wide range of artists including folkie Joan Baez, the Who, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Sly and the Family Stone – a who’s who of ‘60s rock giants. Even Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, who were a newly-formed “supergroup” at the time, and Carlos Santana and his band, whose debut album was released two weeks later and was virtually unknown outside of San Francisco.

The panel discussion focused on the legacy of Woodstock, and I had to admit that I didn’t think it made any real impact on the politics of the day. The anti-war movement was already taking over college campuses, and the “peace and love” hippie vibe wasn’t new – it was sparked by the Summer of Love in San Francisco in 1967. Even the idea of a rock festival wasn’t new, though the huge scale of Woodstock was unprecedented. Monterey Pop in 1967 was filmed for a terrific documentary, and so had the Newport Folk Festival earlier in the decade, which featured Bob Dylan unveiling his electric rock and roll self.

But Woodstock, if nothing else, was a huge gathering that alerted an entire generation of young people that they weren’t alone in questioning authority and rocking out to a new breed of musicians who were like them, not the polished AM Top 40 pop music of the Monkees or the Association.

But you know what? The Association, who performed at Monterey Pop, was the only group of the times that featured an Asian American musician, lead guitarist and singer Larry Ramos, who was Filipino.

There were no Asians rocking it at Woodstock, which for me, is a shame.

Decades later, there was finally an AAPI connection to Woodstock, and one we didn’t get to discuss on the panel. Director Ang Lee (“Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,” “Brokeback Mountain,” “Life of Pi”) released “Taking Woodstock,” a sweet film about a young man whose family’s upstate New York “resort” is turned upside-down by the music festival down the road. The movie was interesting because it recreated footage from the original “Woodstock” documentary — nuns giving the peace symbol to hippies passing by, the man happily cleaning out the port-a-potties — but disappointing because it was about Woodstock without ever showing any of the music at Woodstock.

Still, it was cool to have Lee become part of the Woodstock legacy.

The original version of this post was written for Asian Avenue Magazine.

The photo at top are the Denver Press Club panelists, from left Steve Knopper (Billboard Magazine), me, Alisha Sweeney (Indie 102.3) and Ricardo Baca (Grasslands). Photo by Jude Delorca