22 Apr On “authenticity” in Japanese food

Maybe not surprisingly, I’ve been a stickler for “authenticity” in food—especially Japanese food. I was born in Japan, and I’ve loved Japanese food all my life. I even wrote a book about the history of Japanese food in America, Tabemasho! Let’s Eat!

I’m a foodie who takes #foodporn shots of many of my meals. I love all cuisines and seek out new dishes to try. And I try to make sure that the food I like reflects traditional culture, accurately and with respect. That doesn’t mean that I won’t eat “fusion” food—in our modern, shrinking world where economies are interconnected, you can’t just stop the spread of culinary cultures and say you’ll only eat things cooked in the old ways from the olden days.

Still, in the past, I’ve criticized the dilution of Japanese food cooked haphazardly for profit resulting in poor quality. In the past I’ve called out cultural appropriation.

However, I’ve changed my mind on a lot of these issues over the years.

I’ve become much more aware about issues of privilege and colonialism and how they affect even the food we eat. In my book, I write about the origins of some of what we consider “traditional” Japanese foods, and how things like tempura (Portuguese) and ramen (Chinese) were not originally Japanese. And some of the dishes we cherish as standards of Japanese cuisine, like sukiyaki, wasn’t really eaten in Japan until the late 1800s when people were encouraged to eat more meat after centuries of Buddhist prohibition of beef.

So, food culture evolves. And we can’t always stop it, even if we don’t like it and try to criticize it.

Japanese food, like Japanese culture, has always adapted as times changed. One of the most popular foods in Japan is curry—half of all Japanese eat curry several times a month, and it’s a family favorite at home and in curry chains. Curry came to Japan from India by way of the British, who appropriated it when they colonized India, and the sailors brought it to Japan in the 19th century. But Japanese curry, like everything else Japanese have adopted and adapted to suit Japanese tastes, isn’t like Indian curry, or Thai curry. It’s uniquely Japanese (although, to be transparent, I had a South Asian friend tell me there is a place in India that serves curry that’s very close to Japanese-style).

These concepts of “authentic” and “traditional” have always been placed on ethnic cuisine, noting here that “ethnic” cuisine as a term assumes the person using it is not “ethnic” and therefore white, and anything “ethnic” is foreign, perhaps exotic. That’s certainly how Japanese food was perceived for decades even until the 1980s and ‘90s. My book delves into the evolution of how Japanese food became so mainstream you can find (lame) sushi in supermarkets everywhere.

One related point is that these foods are usually ghettoized into an “ethnic food” aisle in supermarkets. There’s a movement afoot to drop the designation because it makes anything Asian, African or Latinx foreign and the “other” from “regular” food in the grocery store. Why shouldn’t shoyu and Sriracha be right next to Worcestershire Sauce and Tabasco?

Anyway, I’ve recently realized how I’ve been blurring my own lines of “traditional” versus “modern” or “fusion”—sometimes for a damned long time.

I’ve made Kakimochi chips for years from my wife Erin’s auntie’s recipe, mixing sugar, corn syrup, butter, sesame seeds and shoyu over Tostitos mini-tortilla chips – yes, Mexican corn chips. They’re popular with friends and family — and I eat too many of them myself. I give them to neighbors for the holidays. At parties, people have called them “crack chips” because they’re damned addicting.

And of course, everyone’s amazed that they’re baked with tortilla chips, not rice crackers. Fusion snacking at its best!

This week, I found at Trader Joe’s a bag of “Umami Flavored Corn Tortilla Chips” and I first thought “ah-hah! Cultural appropriation!” Umami, the Japanese concept of the fifth taste, savory (after sweet, sour, salty and bitter) has become the food fad du jour. But you know what? The chips are addictingly delicious, and they reminded me that I make my own version of savory snacks using tortilla chips. I’m only sad that these Umami Chips were a seasonal item and won’t be back until next year.

Ramen is another easy example of adapting Japanese cuisine to suit local tastes (or whatever ingredients might be available in the fridge). Yes, you can go out to restaurants and pay $15 for a bowl of ramen. Some of them, like the cheesy spicy “Cremoso Diablo” at my favorite Denver ramen restaurant, Tokio, are definitely not traditional Japanese (Tokio’s more traditional ramen bowls are amazing too).

Instant Ramen is a treasure trove for experimentation and evolution. From the humble origins of Nissin’s original packet of chicken flavored instant ramen in 1958, to the same company’s introduction of Cup Noodles in 1971, not just college students, but several generations of Japanese (and Americans) have grown up eating the simple-to-make, inexpensive hearty noodles. There are a myriad of companies in all parts of the world, not just Japan, making instant ramen these days.

One is a pretty new brand, Chef Woo, named after a famous chef, Song Wu Sao of ancient China, but based in South Carolina. What sets Chef Woo’s instant ramen apart is it’s 100% plant-based with no animal products, including its chicken and beef flavors. Try some if you see it in your store, or check out https://chefwoo.com/.

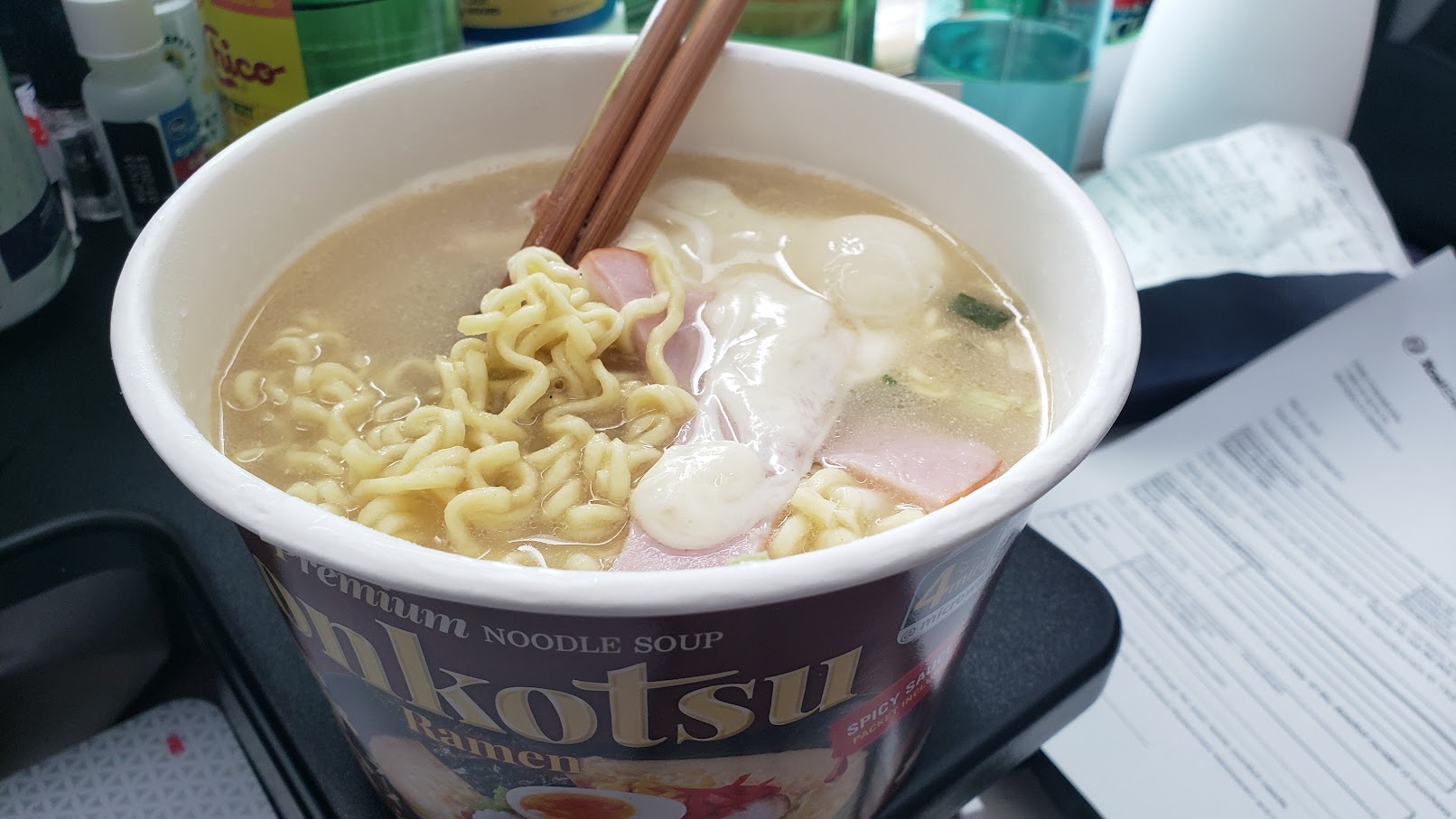

Meanwhile, I love the Korean-made Nongshim brand’s Tonkotsu bowl-o-ramen, which I buy from Costco. It really has a satisfying tonkotsu pork broth flavor. I’ve found myself adding my own protein to the ramen and wandered farther and farther from my snooty “traditional” Japanese standards. Last week I had it with slices of Canadian bacon and Italian provolone cheese (photo at top of post). It was delicious, and filling multinational treat. I’ve also topped the instant Tonkotsu with homemade Chashu, which is more “traditional” and super tasty.

I just learned from a food critic in Austin, Texas about a place I’ve got to try if I ever get back to the Lone Star state: Ramen del Barrio.

The chef is white, New England-born but trained in Japanese restaurants. And being in Austin, he fell in love with Tex-Mex ingredients. The one I have to try is Ramen with Menudo. That sounds like the kind of combination that I’m surprised Japanese haven’t already tried, since there’s a cultural tradition of eating every part of an animal including beef tongue and offal. Menudo, a traditional Mexican dish made with cow tripe (stomach lining) but served with Latin spices and ramen noodles and soup, sounds like a culinary match made in heaven.

Food is truly the gateway to culture… and community!

This post was originally written for and an edited version published in the Pacific Citizen newspaper of the JACL.