27 Sep The Death of “Tokyo Rose”

Iva Toguri D’Aquino died Sept. 26, 2006 at age 90, in Chicago. You might not know her, or remember her today, but she was a victim of circumstance who was once one of the most hated women in the United States.

Iva Toguri D’Aquino died Sept. 26, 2006 at age 90, in Chicago. You might not know her, or remember her today, but she was a victim of circumstance who was once one of the most hated women in the United States.

You might not know her, but you might know her nickname: Tokyo Rose.

For many, the name evokes a Mata Hari-style enemy agent, who was convicted of treason ad imprisoned after World War II. Even if people do recall the name Tokyo Rose and her evil association, I bet most don’t recall that she was vindicated and won a full presidential pardon decades later, for the unfair way she was accused and tried.

Iva Toguri was a Nisei, a second-generation Japanese American who was born and raised in Southern California. She was raised as an all-American girl: a Girl Scout who couldn’t even speak any Japanese.

Just months after receiving her zoology degree at UCLA, in July, 1941, she traveled to Japan to care for an ill aunt. Her timing was lousy — a few months later, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and she was trapped, along with thousands of other American citizens, in Japan.

Because she was an enemy alien (she refused to give up her U.S. citizenship), she wasn’t entitled to the rationing coupons handed out by the Japanese government, and she was even kicked out by her aunt and uncle, for being pro-America. She was hounded by the kempeitai, the secret police, and had to scramble for work. She was befriended by a group of POWs who were forced to work for Radio Tokyo, a propaganda arm of the Japanese government.

When the station needed an English-speaking woman to taunt American troops, Toguri was recommended and got the job. Working with her friends, she made their “anti-American” broadcasts so outrageous that she hoped listeners would know she wasn’t serious.

She never used the name “Tokyo Rose.” In fact, there was never any woman who used that name in any Japanese propaganda broadcasts. Toguri went by the name “Orphan Ann.” “Little Orphan Annie” was one of her favorite stateside comics, and she felt truly orphaned in Japan. She married Felipe D’Aquino, a Portuguese citizen, in April of 1945, and declined to take his citizenship, preferring to stay an American.

Fate dealt her a terrible hand after the war ended that summer. When the U.S. occupation forces arrived, she made the mistake of agreeing to identify herself as “Tokyo Rose” for an American magazine reporter, even though she didn’t use that name in her broadcasts, and even though there were about a dozen American women stuck in Japan during the war who worked for Radio Tokyo. The reporter offered to pay her and her husband $250 — a significant amount of money for the time, especially in a poverty-stricken country like Japan, and she welcomed the chance to tell her tell the story of how she remained patriotic despite her circumstances.

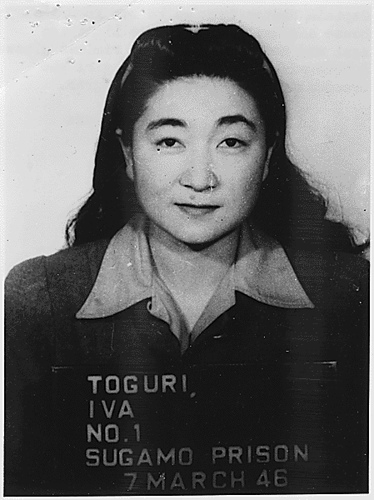

Instead, the reporter handed her “confession” to the Occupation administration, and she was arrested and held for months in Sugamo prison with Japanese war criminals. She was ultimately released for lack of evidence, but thanks to a series of unrelenting attacks by American newspaper and radio gossip columnist Walter Winchell, she was re-arrested in 1948 and taken back to the U.S. No other broadcasters, including U.S. citizens stuck in Japan, or the American and Australian POWs who helped write the scripts for “Tokyo Rose,” were arrested.

She was found guilty in a 1949 trial of one count of treason, for talking about the loss of U.S. ships over the air. She was fined $10,000 and sentenced to 10 years in prison. She was released after 6 years for good behavior. She went to work for her parents’ import business in Chicago in the 1950s and lived a quiet, private life. She never saw her husband, who had remained in Japan, again, and the two divorced in 1980.

It was only in the 1970s when she was able to find supporters who helped research the injustice and were able to prove that witnesses were forced to lie about her, and eventually, Gerald Ford signed her full pardon — it was his final act as president.

Ultimately, “Tokyo Rose” is a footnote to the history of Japanese Americans and to the history of World War II. But Iva Toguri D’Aquino’s death closes the book on an example of trial by media and a government willing to ignore constitutional rights in the name of “justice,” themes that still seem to play out today.