16 Aug The Olympics are a celebration of pride — so we should never forget the JA who set records in the 1950s

I’ve been watching the Olympics when I get tired of obsessing about the presidential campaigns. I’ve been a fan of the Olympic games since I was just a kid – I remember vividly watching the 1964 games in Tokyo when my family lived in Japan.

(Photo courtesy of the Center for Sacramento History Sacramento Bee Archives)

I was not quite 7 years old at the time, and the coolest part of that year’s competition was that my dad took the whole family on a day trip on the new “Shinkansen” Bullet Train, the fastest in the world, from Tokyo to Osaka and back. I remember the hubbub over the Olympics because Japan was even more hyped about that year than the Tokyo games coming up in 2020.

In October of 1964, Japan was to host its first-ever Summer Olympics. The honor was originally scheduled for 1940, but those games had been first oved to Helsinki, then cancelled entirely because of the conflict already engulfing Europe and the tensions with Japan over its invasion of China, a major step towards the start of World War II in 1941.

After its defeat in 1945, Japan had been focused on rebuilding and modernizing, and by 1964, the country was ready to show itself off as a member of the world’s first tier of nations. Facilities including an iconic stadium were built, and the entire country, not just the city, was abuzz with anticipation.

We didn’t see any of the games live, but I remember we watched every day on our flickering black and white television sets.

Later from the US, we watched the 1972 Winter Olympics which were held in Sapporo, Japan – the first winter games to be held in Japan. My mom is from Hokkaido, the prefecture where Sapporo is, so we were glued to the (color) TV for those games.

The Olympics is a showcase of the world’s greatest athletes, but let’s face it, it’s also a chance for all of us to feel proud of our own countries (or countries where we have roots). There’s an element of patriotism that creeps close to nationalism. I’m proud of the US athletes who’ve medaled in Rio de Janeiro, especially the athletes of color who are making their mark on the world stage, or track, or court, or pool. And who isn’t amazed by Michael Phelps, who’s overcome personal adversity to extended his legacy to retire on top of the swimming world?

But fame is fleeting, and some of the greatest athletes in the world can become forgotten heroes over time.

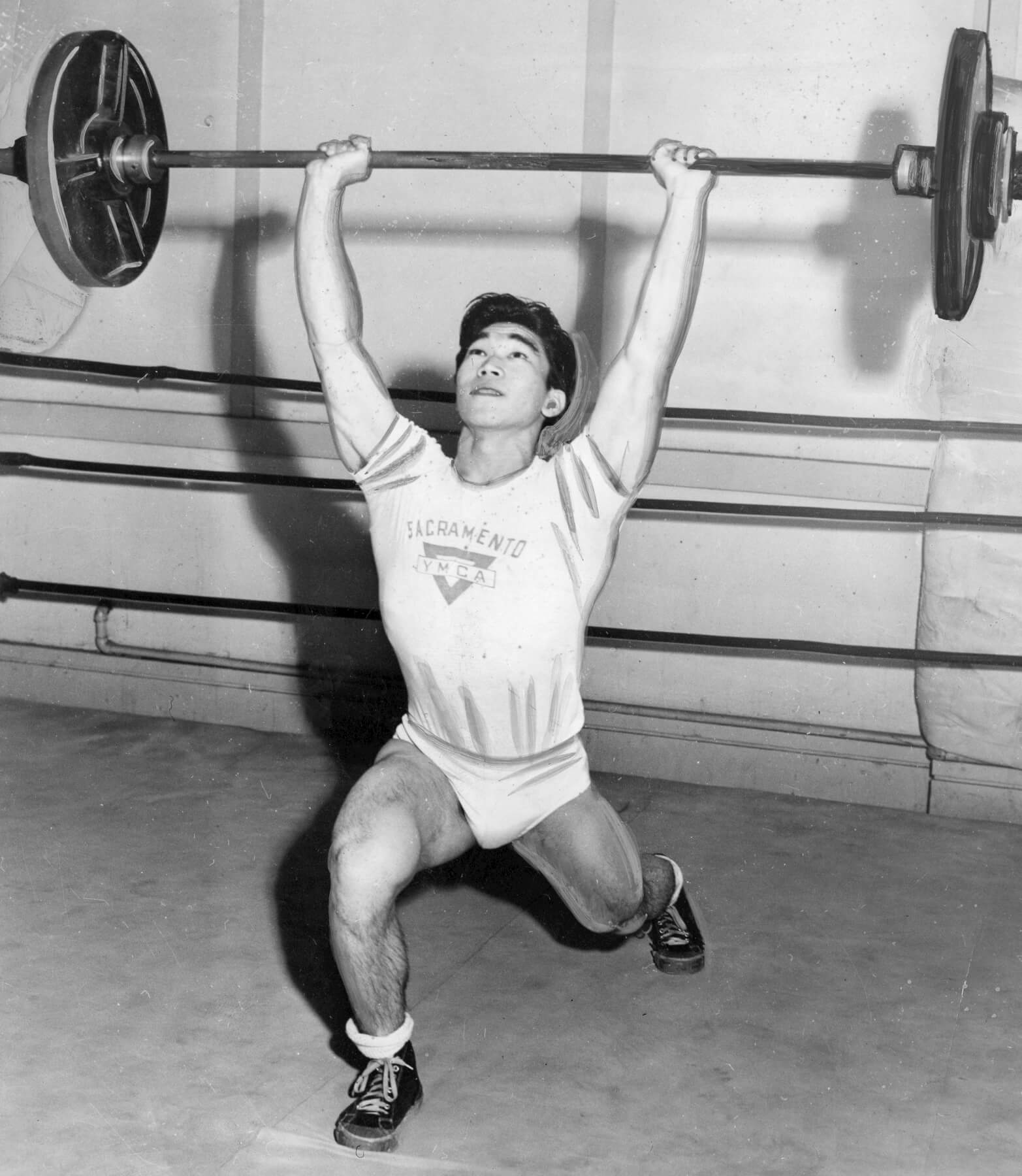

How many people know the name Tommy Kono today? A Nisei athlete who was unknown at the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, he won the Gold in weightlifting and set a new Olympic record while he was at it – by 20 pounds more than his closest rival, from Russia. But today?

When TV reporter Ryan Yamamoto saw the name Tommy Kono in 2012, he wondered, “who?”

Unfortunately, most people today might ask the same question about Tommy Kono. But thanks to Yamamoto and his wife and fellow TV reporter Suzanne Phan, Kono’s legacy has been captured in a half-hour documentary, “Arnold Knows Me: The Tommy Kono Story,” that’s making the rounds this month on PBS stations across the country, just in time for the Rio Summer Olympics.

Kono was a Japanese American athlete who was a gold medal weight-lifter during the 1950s, and one of the most influential athletes in the history of the sport.

Yamamoto asked about Kono because a high school weightlifting tournament in Sacramento, where Yamamoto and Phan worked, was called the Tommy Kono Classic. When Yamamoto noted the name, the organizer asked, “’You want to meet Tommy?’ Tommy who, I asked. I didn’t know who he was.”

After he was told about Kono’s achievements, Yamamoto says, “I was like that’s impossible. If he was that great, I would know about him. That’s an incredible resume. As a sportscaster, and as a Japanese American, I was embarrassed that I didn’t know who this guy was.”

So Yamamoto met Kono, who had long since retired to Hawaii and flew to Sacramento every year for the tournament named after him, and filed a report about the champion. The report chronicled Kono’s amazing career: Two Olympic gold and one silver medals starting with a gold in 1952; eight World Weightlifting titles; 25 world records; seven Olympic records; and for good measure, one Mr. World and three Mr. Universe bodybuilding titles.

What was most amazing about Kono’s achievements is that he had been imprisoned with his family in an American concentration camp during World War II, along with 110,000 other people of Japanese descent. Kono was born in Sacramento, but his family had been rounded up and sent to Tule Lake in northern California. That was where the skinny 12-year-old overcame his early asthma and grew into an athlete, and where he first began weightlifting. He was drafted by the Army and would have been sent to fight in Korea, but the military noted his talent and allowed him to stay home to compete in the 1952 Helsinki games.

After Yamamoto met Kono and filed his first story about the champion, he wondered if he could create a longer story about the medalist. The idea “sat on the shelf for a couple of years,” Yamamoto admits, until he was included in a leadership program of the Asian American Journalists Association. During the leadership program, Yamamoto was asked, “what’s your dream job?”

“I would like to do something long-form, something meaningful, more than a minute-thirty (long, the typical length of a TV news story),” he says. He realized he already had the seeds of his dream project: he brought the Kono story off the shelf in 2012, and began fleshing out the idea. He and Phan had help with the project from a mentor, David Hosley, who was the general manager of the station where they both worked. Yamamoto is listed as director and Phan as producer, with Hosley named executive producer.

“We’d hit road blocks and he said OK, talk to these people, and give advice,” Yamamoto says of Hosley, who he and Phan consider a mentor. “He helped me a lot.”

“He warned us this would be the tough part of the job,” adds Phan — making a documentary film isn’t like a TV report, and has to ebb and flow and tell a story slowly.

The project finally came together in 2015, when the couple found support from public television stations who set a deadline of airing the finished film during the 2016 Olympics. Like all journalists, Yamamoto and Phan responded to the deadline pressure. They flew to Hawaii for one final interview with Kono, and funded the rest of the filming and editing through credit cards and a GoFundMe.com campaign. The 27-minute film is available on DVD through the website but they’re not aiming to make a profit, and are still accepting donations to help pay their debts.

“If we come close to breaking even, that’s huge. I consider it a big win already,” Yamamoto says.

The couple now work in Seattle, both at TV station KOMO. Kono sadly passed away in April 2015, without ever seeing the film, but his family flew to Sacramento for a premiere screening this summer.

Not only was Kono the greatest American weightlifter and an inspiration to generations of lifters who’ve come after him, he inspired the man whose name appears in the film’s title. Arnold Schwarzenegger acknowledged that he was inspired as a teenager to follow in Kono’s footsteps after seeing Kono in Vienna. He had a photo of Kono on his bedroom wall, and when he was Governor of California and learned Kono would be in the state attending a tournament, he arranged to meet his hero. The documentary includes footage of Schwarzenegger praising the elderly Kono.

With a sly smile and a laugh, Kono says in the film, “Lots of times people would say, ‘Do you know Arnold?’ Meaning Arnold Schwarzenegger, I would say, ‘What do you mean? Arnold knows me!”

With the world’s attention on the Summer Olympics, Yamamoto and Phan have created a quiet tribute to the legacy of a largely forgotten pioneer, the first Asian American gold medal weightlifter and body building sex symbol — an Asian acknowledged as the “most beautiful man in the world.”

And, someone who Arnold Schwarzenegger looked up to as a role model. That’s some heavy legacy to shoulder!

Here’s the trailer for “Arnold Knows Me: The Tommy Kono Story”: