01 Feb Is Naomi Osaka Japanese enough for Japan?

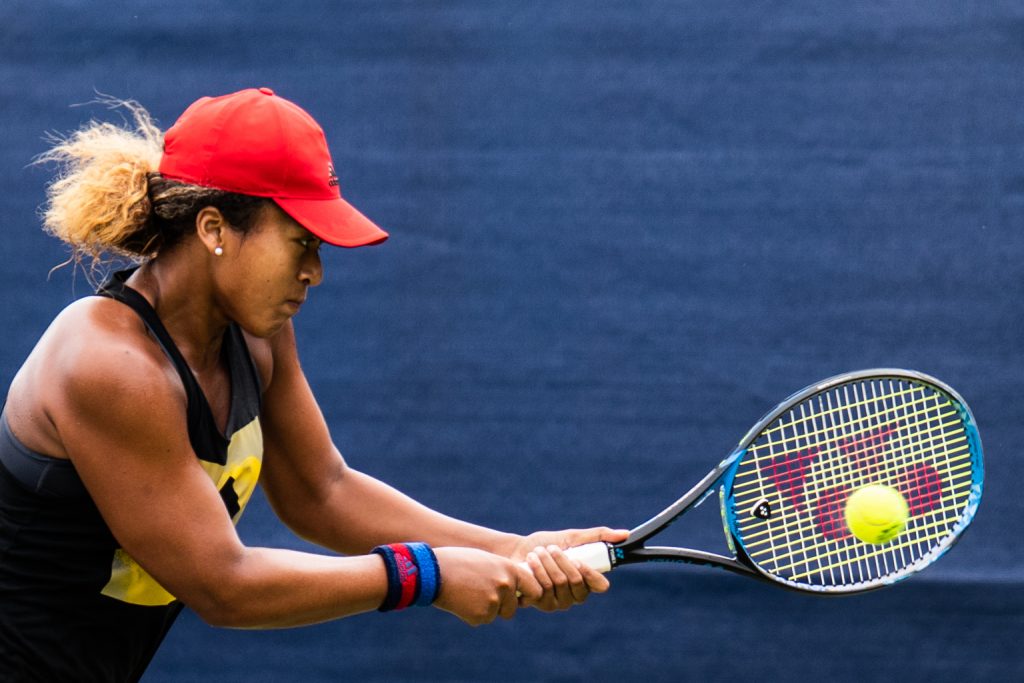

Naomi Osaka at the 2018 Nottingham Open qualifiers, photo by Peter Menzel, Creative Commons/flickr

Naomi Osaka at the 2018 Nottingham Open qualifiers, photo by Peter Menzel, Creative Commons/flickr

I love following the exciting young career of Naomi Osaka, the world’s first Japanese tennis star who has been ranked number-one by the Women’s Tennis Association, after her recent win in the Australian Open.

I love her passion and skill and determination to win. And most of all, I love that she is mixed-race, with a Japanese mom and Haitian dad. And, that she’s culturally as American as she is Japanese or Haitian.

She was born in Japan, and her family came to the U.S. when she was just three years old. They first lived with her father’s family in Long Island, New York, and by the time she was 10, the family (which includes an older sister who also competes in tennis) moved to Florida, where they still live.

Osaka claims both American and Japanese citizenship. She’s 21 now, and the media have begun pointing out Japan’s citizenship law: At 22, Japan doesn’t allow dual citizenship. Naomi will soon have to choose her nationality.

Her sister Mari, who’s already 22, is still listed as playing for Japan by the International Tennis Federation. The sisters have represented Japan even though they’ve been mostly raised in the United States because, as explained by their mom, they “feel” Japanese. It may have helped that the U.S. Tennis Association wasn’t interested in Naomi until she started to gain attention as a rising star. When the USTA invited her to join them, Osaka declined.

Now, she has sponsorship deals like any American athlete might. Except, of course, she’s representing Japanese companies. Nissin, for one — the company that invented instant ramen in the 1950s and Cup Noodles in the 1970s. Unfortunately, Nissin had to apologize recently for an animated TV commercial that gave the athlete oddly lightened skin, and was accused of whitewashing the star.

Which brings us to the most striking part of Osaka’s stardom: She’s biracial Japanese and black. Most Japanese, especially the media, have embraced her for showing the world that a tennis player from Japan can be great. But she’s received some flak from racists in her chosen country — and not just for the color of her skin. It may be a further challenge that like many of us Japanese Americans, she can understand some Japanese but can’t speak fluently.

So far that hasn’t hurt her, though. When a reporter asked her to respond to a question in Japanese, she replied in English… and her fans blasted the reporter for being rude and un-Japanese.

Unfortunately, other biracial stars in Japan have faced prejudice.

The Pittsburgh-born singer Jero, who is African American and Japanese, moved to Japan and had a 10-year career as an “enka” star, performing the style of music that can be described as a mix of Japanese blues and big-band pop. He was treated as a novelty, gaining gasps and applause when he was introduced during the early part of his career. Last year, he announced he was putting his singing career on hold to become a computer engineer, which is what he had studied in college.

Ariana Miyamoto, a half-black, half-Japanese woman from Nagasaki, made headlines when she won the Miss Japan title in 2015. At the time, the media made a huge deal of her ethnicity and she had to deal with a lot of racism. She used her one-year reign to speak out about prejudice and for biracial Japanese. Ironically, the 2016 Miss Japan was also biracial, Japanese and Indian.

A powerful documentary, “Hafu,” looks at the plight of biracial people in Japan and the challenges they face in a society that has historically valued racial homogeneity. It’s available on Amazon Prime and worth watching.

Arudou Debito is a Caucasian American who moved to Japan to teach and married a Japanese woman, changed his name (he was born David Ardwinkle) and nationality, and became an expert on racism in Japan. He warned Osaka in a Japan Times commentary that even without the challenge of her identity, Japanese fans have been brutal on top athletes who peaked and couldn’t regain their heights. Adding her mixed ethnicity, he predicts, will be a tough challenge to overcome.

In another Japan Times commentary, former diplomat Kuni Miyake points out that xenophobia exists in every society, and Osaka represents contradictions in modern Japanese society and raises the question of who is Japanese. In the end she notes that Japan is naturally becoming more multicultural, and Osaka conducts herself with a humility that is deeply, well, Japanese.

But being ranked at the top of the world helps. Let’s hope Osaka can keep winning and maintain her star status.

It could be really interesting to follow her career if she chooses to become an American athlete in October, when she turns 22. Would her Japanese fans continue to love her?

Let’s hope so. But myself, I’m hoping she chooses Japanese citizenship. I think her celebrity in Japan can help change some attitudes about race across the Pacific.

This post was originally written as a Nikkei Voice column for the Pacific Citizen, the national newspaper of JACL.