27 Oct “We Are Not Free” tells the JA incarceration story through a different perspective

During the Coronavirus pandemic, we’ve all gotten used to staying home every evening – no parties, dinners at restaurants, movie nights, concerts. Just a lot of plopping down on the couch to see what’s available on demand via cable, Netflix, Amazon Prime or other streaming source that brings entertainment to your living room. A lot of people have been reading too. Book clubs seem to have been embraced by a whole new crop of eager readers.

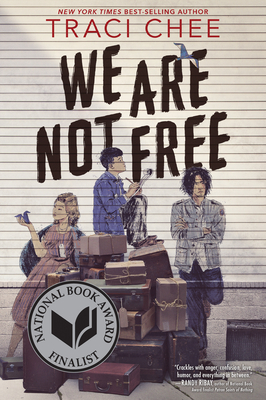

I was honored this spring to be asked to create an educator’s guide for a novel so that teachers could use the book help students learn about the Japanese American incarceration experience. “We Are Not Free” by Traci Chee, is an excellent novel, written for “Young Adult (YA)” audiences but it’s a terrific read for grownups of all ages too.

It’s a powerful, emotionally gripping book that’s fiction but based on memories of Chee’s family members and their friends.

The story begins with a group of 14 Japanese American friends in San Francisco’s Japantown in the early months of 1942, as they watch the panic and confusion over Executive Order 9066 and the coming evacuation of the community to who-knows-where. Chee tells the story through the perspectives of these friends and siblings who are taken from their familiar surroundings, first to a temporary detention center where entire families had to share horse stalls at the Tanforan Race Track south of San Francisco, and then on to two separate camps, Topaz in Utah, and later, Tule Lake in northern California. She tackles the community’s issues of loyalty and loss, and the understandable seething rage in some of the teens, with each chapter told from the point of view of one of the characters.

The different voices represented by this tight-knit group of friends, and the way their relationships evolve over time, connect in a compelling narrative. Some of the relationships are tested by their families’ differing political views and by distance as families are sent to Tule Lake and some of the young men go off to war to prove their patriotism.

Chee captures historical details with sharp, unblinking accuracy, and her deep research vividly brings to life the day-to-day life of the characters. The author’s writing is taut, clean, evocative and often poetic, and although it’s a YA book, any adult reader interested in issues of history and social justice should make “We Are Not Free” required reading.

“We Are Not Free” is a must-read for anyone who’s interested in Japanese American history, and how its impacts still manifest today.

Chee’s favorite character in the book – the one she identifies the most with — is Mary, a 16-year-old whose family gets moved to Tule Lake because her father and brother didn’t say “yes” to the two key questions on the “loyalty” questionnaire.

“Yeah, she’s the one that speaks to my high school me,” Chee says. Because the “disloyal” prisoners could be deported back to Japan, Mary had to speak Japanese, learn the arts and crafts and culture of Japan. “… some of the other girls love it, but I spend most of my time reading books under the table and fantasizing about putting a pair of hashi through my eyes.” Chee researched the details of day-to-day lives in the concentration camps and then added her quirky sense of humor and effortless way with dialogue and storytelling throughout the book.

“I feel like there is an intelligence in Mary, where she sees how unjust her situation is,” Chee says. “But like many teenagers, she doesn’t really have a way to change that situation. In the case of Mary, she didn’t have access to a loyalty questionnaire, she couldn’t have answered for herself because she was a little bit too young, she was stuck under that 17-year limit. And so she’s forced to go to Tule Lake and she sees how wrong it is.

“But at the same time she has this resentment and this intelligence, she also is smart enough to know that like, is there any good outcome here? Could they have made any other decision than this? Would she have made a different decision if she had been in that position? And so that’s kind of her arc.”

Chee adds that’s why she identifies with Mary. “So that mostly spoke to teenage me because I felt like I was smart enough and knew what I was about. And also, I felt a little bit powerless in my situation. I just had that kind of rebellious. Little bit of punk rock spirit in there. I think Mary has that.”

There were other characters who were based on elders she interviewed during her research.

The blithe spirited fashionista Hiromi, or “Bette” as she called herself after the movie star Bette Davis, was based on Chee’s grandmother. “She has a kind of buoyancy,” Chee says. “And her desire to live a life of glamour and excitement despite the fact that she is in an incarceration camp was absolutely inspired by my grandmother. My grandmother wanted to do just a ton of activities and tried to be as much as possible, you know, a regular American teenager.”

These real-life personalities jump off the page and draw readers into their stories. Her grandfather was one of the personalities she captured in the book, although not as a specific character.

“The first time I learned about incarceration, I was 12,” Chee recalls. “It was at a ceremony that the San Francisco Unified School District was putting on in 1997 for incarcerees who would have graduated in San Francisco if they hadn’t been forcibly evicted from their home. My grandpa was one of them. And the Chronicle did this write up on it. And in that article, he was quoted as saying, ‘We were the bleeding hearts in 1942.’ That was my first encounter with incarceration, and that kind of anger and resentment with like a little bit of humor in there, I think, really impacted the way I thought about the incarceration.

Her grandfather isn’t represented by one of the group of friends, but Chee says the passage where the JAs were evicted from Japantown was inspired by photographs of her grandfather.

“There’s a scene in that chapter where (Shig, one of the older boys) is sitting on the steps across from the civil control station in J-Town watching all these people line up with their luggage, and that’s all they have. They’re waiting to be shipped off. And that scene is inspired by photographs of my grandfather, that my mom and my grandpa saw when they were at the Smithsonian Museum, around 1997, around when I was in middle school, and she was telling me the story of them walking through the Smithsonian. And my grandpa goes, ‘Oh, that’s me.’

“That’s kind of one of her memories of learning about the incarceration. And so when I started interviewing relatives, she was telling my relatives about the story. And I was like, I could find that photograph. And so I did. I found it. I gave it to her as a present. Yeah, and that’s one of the times when I looked at him, he was so young. And I was like, that’s one of the things that stuck with me from that photo is that he’s really just a kid.”

Chee’s family roots for the stories in the book helped her write about the past with the vividness of the present.

“It came out of, you know, those experiences of seeing my grandpa’s photo from 1942 during the eviction, and seeing how young he was, and then like reading his letters to my grandma, where he talks about yearbooks, and the dirt on their friends, and who she’s going out with. And he told stories in those letters about how he learned to drive in camp, and the commissary trucks that would deliver food to the mess halls, and he crashed one of them into one of the barracks.

“I felt like these are just such teenage things. It’s just part of the American teenage experience. And that things didn’t feel like they had changed that much from the 1940s to when I was a teenager, and then I imagine it’s not that different now. These concerns and the way that they interacted with their friends felt like that could be universal, and that could be a way into the history to make it feel alive and immediate and urgent.

“Because also, the problems of 1942 aren’t gone in 2020, either. So I hope that that helps to make people feel like, you know, racism and social problems, detention centers are still a problem. We have not solved these. And so kids today also are going to be having to deal with those things just like they were having to deal with the things in the 1940s.”

And those young people today can read “We Are Not Free” to get an understanding of how those long-ago problems, and see how they persists today. Thanks go to Traci Chee for capturing this story in such a compelling, powerful way.