03 Mar Remembering Denver’s Chinatown roots in the midst of renewed anti-Asian hate

Hate crimes against Asians are on the rise. Again.

But this time, there’s a difference from last year’s wave of hate: The “mainstream” media, from newspapers to television news, has been reporting on the spike. Hate crimes against Asians in America are nothing new, and certainly the numbers became noteworthy with the coming of the coronavirus pandemic and political leaders like the former president calling it the “China Virus” or “Kung Flu.” The media covered some stories last year but didn’t fully treat the outbreak of racism as a tragic side-effect of the coronavirus.

The difference now, a year after the pandemic began, is the ferociousness of the attacks and how elderly Asians have been targeted, and the fact that more Asians and Asian Americans are willing to speak out about their experiences. There’s been a year of consciousness-raising and urging our community members to call out incidents. Before, it was difficult to get even young AAPIs to report to law enforcement; now it seems like more of us are willing to be on the record with cops and journalists. That’s good.

A lot of these crimes are happening in broad daylight and surveillance videos captured many of them, including a man in Oakland being pushed to the ground from behind and a woman in New York City being punched and kicked. There were seven attacks against Asians and Asian Americans in New York during a two-week period, including a 36-year-old man who was stabbed in front of a federal courthouse. An 84-year-old man in San Francisco died of injuries after being violently pushed to the ground. In January, a woman was shot in the head by a flare gun during Lunar New Year celebrations in Oakland. In February, an 86-year-old grandmother was assaulted and robbed in San Jose.

Amidst this wave of attacks, a group of Asian Americans in Denver calling ourselves the Re-envisioning Denver’s Historic Chinatown Project have been working to remind people that the level of hate against Asians existed even in the earliest days of Asian immigration to this country.

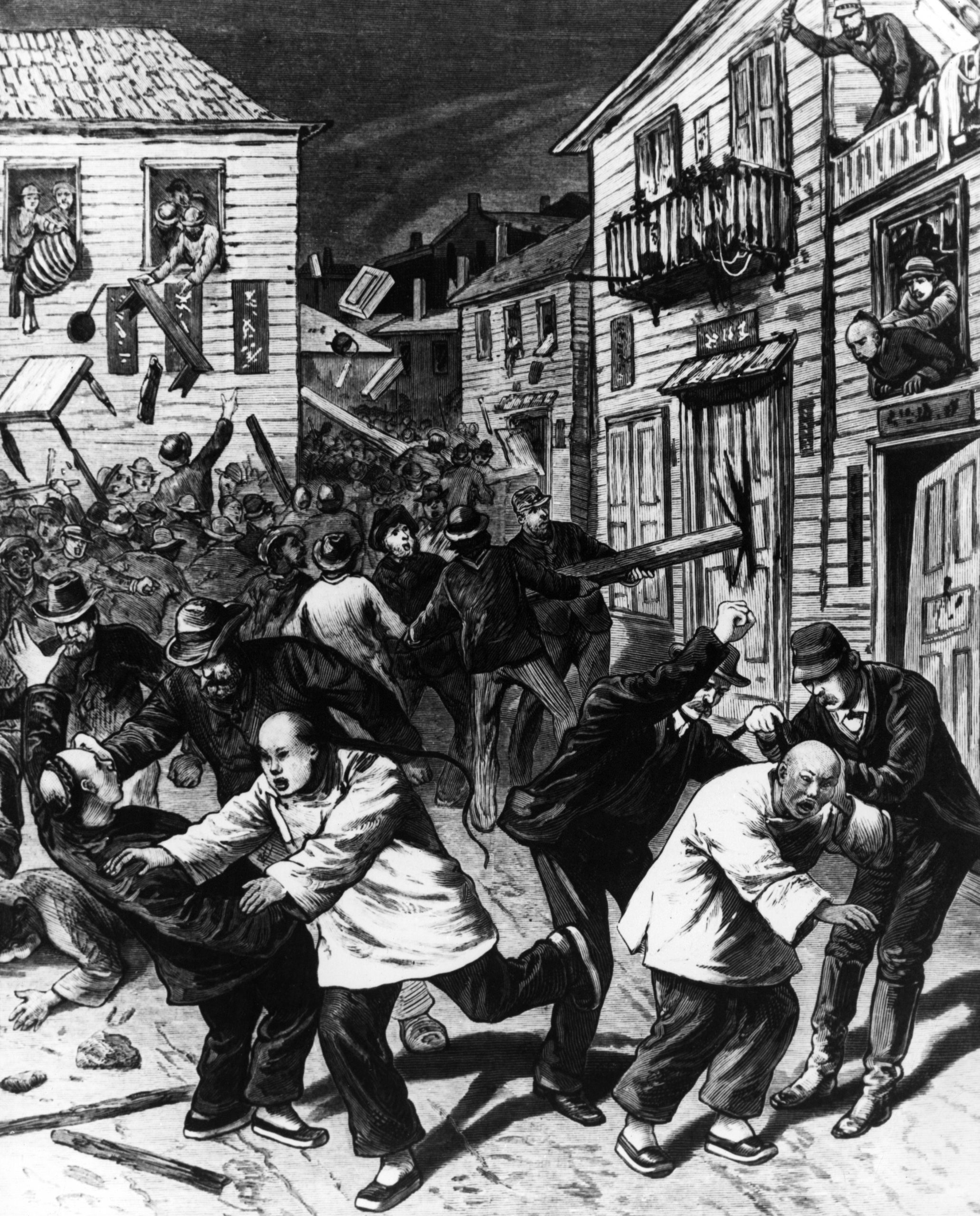

On October 31, 1880, there was an anti-Chinese race riot in Denver that left businesses and residences destroyed in Denver’s now-forgotten Chinatown district. One man, Look Young, was beaten to death and then hung from a lamp post, and many others were injured. None of the over $50,000 of damage and property was reimbursed. (The illustration above of Denver’s anti-Chinese race riot of Oct. 31, 1880, was by N.B. Wilkens and it was published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 20, 1880.)

The riot was sparked by a bar fight in a pool hall between two Chinese men and four white men. The fight poured into the streets and alleys of downtown Denver and within a couple of hours thousands of white folks stormed through the ethnic enclave – in what’s today called Lower Downtown, or LoDo — busting in windows and chasing the Chinese out.

This race riot was used as an example of why Chinese should no longer be allowed to come to America, and in 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, to this day the only law barring immigration to the US by a population’s country of origin.

The riot didn’t completely rid Denver of what had been a thriving Chinatown district. The first Chinese arrived in the 1870s, after the Trans-Continental Railroad was completed in 1869. Tens of thousands of Chinese laborers worked (and many died) on the railroad but weren’t allowed to participate in the celebration and photo op at Promontory Point, Utah when the locomotives from the east and west coasts met.

After that, the laborers settled throughout Utah, Wyoming and Colorado. Many worked in mines in the mountains. And many came to Denver, the biggest city in the region, and settled not far from Union Station where they disembarked, in the bustling part of what passed at the time for “downtown.” They started businesses along the alleyways of LoDo including laundries and unfortunately, opium dens. Those opium dens served Chinese, but many white addicts also visited them. Because of the drug, which was called “hop” by users, whites referred to the district derogatorily as “Hop Alley.”

But the area wasn’t just about drugs. Chinese lived and worked there and established a cultural hub. Even with Chinese immigration closed off, Denver’s early Chinatown was part of Colorado’s ethnic mix into the late 1800s.

By then, the Japanese had been invited as the next wave of cheap immigrant labor from Asia. In 1900, the Census noted all of 10 Japanese in Denver. But by 1910, there were 585 in Denver (over 2,300 throughout Colorado). Like the Chinese (and the Black and Latinx communities), the Japanese settled in certain parts of town because of “redlining” laws that controlled who could live where. The Japanese took over part of what had been Chinatown, and then spread out from downtown for blocks and operated dozens of businesses in the post-WWII years along a stretch of Larimer Street.

Today, LoDo is thriving again but not because of an ethnic identity. It’s anchored at one end by Coors Field, the ballpark where the Colorado Rockies baseball team plays, and is bookended by Sakura Square, the hub of the contemporary Japanese American community. Union Station, the other bookend has been redeveloped into a hip monument to shopping and dining, and LoDo overall is Denver’s restaurant, bar and nightclub district –at least, until covid came calling.

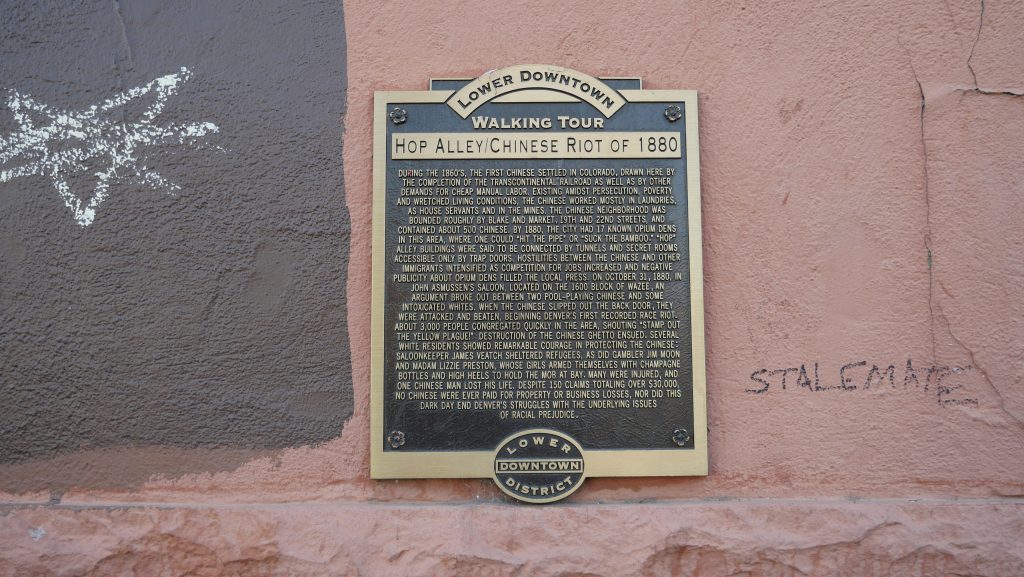

A small plaque attached to the wall of a building kitty-corner from Coors Field at the bustling intersection of 20th and Blake Streets is the only reminder of the Chinatown district.

The plaque is part of a “Lower Downtown Walking Tour” and is titled “Hop Alley/Chinese Riot of 1880.” It describes the Chinese district of the time but focuses on the opium dens and the negative “hop alley” reputation. It describes the fight that started the riot, and notes that “one Chinese man lost his life” without mentioning his name, but then goes on to name the white people who saved fleeing Chinese by letting them into their businesses, including a whorehouse madame. I applaud that white people rescued some Chinese, but the description strikes me as a classic example of history written from a white-centered perspective, emphasizing the white saviors over the victims. The title should not focus on “Hop Alley” and should make clear at a glance that it was an anti-Chinese riot.

At the time I was a member of the Denver Asian American Pacific Islander Commission, or DAAPIC (I rolled off after my six-year stint in December) and the commission agreed to make it a priority to replace this plaque with a more accurate and more appropriate plaque that would commemorate the historic Chinatown district and note the anti-Chinese race riot. I helped draft a proclamation that was given by Denver Mayor Michael B. Hancock last year for the 140th anniversary last October 31. That announcement got some media attention, and since then the effort has grown into a project led by a group that also includes former DAAPIC commissioners (me) and a couple of respected historians and academics, and a couple of architects.

The group took a walking tour of the district given by Dennis Martinez, an amateur history buff who’s done an amazing amount of research about the Chinese roots of Downtown Denver. Through him, I learned that the LoDo building where I got my first journalism job, as music editor and reporter for Denver’s alternative weekly newspaper Westword, had once been a Chinese community center in the 1800s!

Our immediate goal is to replace the plaque, and we already have some funding from Molson Coors, whose name graces the baseball field, and the support of Lower Downtown Denver’s business organization to find artists to paint a mural (or murals) on the large wall of the building where the plaque is mounted. We’ll need to raise funds to get all this done.

We also want to eventually place other markers to note Chinatown locations (including where Look Young was killed) and interactive kiosks to educate people, and years down the line, an Asian museum – (maybe in the building that had been a Chinese community center!). We also hope to launch annual Lunar New Year celebrations in the district. Eventually, we hope some Asian-owned businesses will return to LoDo. We don’t want to replace the current businesses that have made LoDo such a popular entertainment and dining destination, but as buildings are vacated, wouldn’t it be cool to have some Asian restaurants and shops?

This is a long-term project. Nothing will change overnight, except hopefully the plaque. But it’s heartening to be involved in a project like this that reflects and remembers the hardships that Asians faced a century and a half ago, and to use that memory as one remedy for fighting the hatred that we still face today.