08 Jul Tokyo’s second Olympics will be forever remembered for its unique circumstances

As I write this, the “2020” Tokyo Olympic Games are just two weeks away. It’s the second time the summer games have been held in Japan. I was a kid living in Japan when Tokyo hosted its first Olympics, from October 10-24, 1964.

It was a big deal for all Japanese, and for me and my family – a Hawaii-born Nisei dad working for the US Army, my Issei mom from Hokkaido and my older brother and me (a younger brother would be born Oct. 29, less than a week after the games’ closing). I was six years old, and aware that the Olympics were really important for Japan. World War II was still less than a generation in the past, and the country had been rebuilt with incredible energy and focus after incredible devastation – including a firebombing of Tokyo by almost 300 American bombers in one night during March 1945 and of course, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August, 1945.

The timing of the Olympics was perfect.

Japan’s government had been remade by American Occupation into a parliamentary democracy with a constitution. Its economy had struggled, but industry and agriculture were back on track. Japan was beginning to build a reputation for electronics and advanced technology, instead of its earlier reputation for low-cost manufacturing (“made in Japan” was once considered negative). Its cities had been repaired and rebuilt. A 1961 hit song by singer and movie star Kyu Sakamoto, “Ue O Muite Arukou,” had been renamed and became a 1963 number-one hit in the US as “Sukiyaki.”

Japan was going worldwide. There was a sense of optimism in Japan about the 1964 Olympics. It was a coming-out party for the country as it stepped into the spotlight of the world stage.

To prove its industrial strength and embrace of modernization, the country unveiled the Shinkansen – the Bullet Train –as the crowning achievement of its already extensive and famously reliable railroad system. The Shinkansen was planned and constructed starting in the 1950s, but the first high-speed train line in the world began running between Tokyo and Osaka on October 1, 1964 – just in time for the Olympics.

My dad took us on the Bullet Train in its early months for a thrilling four-hour day trip to Osaka and back. What an accomplishment!

My dad also got a medallion that celebrated the Tokyo Olympics, which our family proudly displayed ever since in our homes. (See above.) I have it now, and on its back is a Japanese inscription with the logo for National, one of the Japanese corporations becoming famous worldwide for its quality electronics products (we know it today as Panasonic). So it may have been a souvenir promotional item provided by the company, not a commemorative medallion. But hey, it’s cool and though it’s a bit roughed-up around the edges, I’m glad we still have it. My dad would be glad too.

I remember watching as much of the Olympics as we could on the fuzzy black and white television set in our home in the Ogikubo district of Tokyo. I don’t remember much of the competitions or who won what, but I shared the excitement that was in the air throughout Japan to be hosting the games. I know now that the US had a Judo team that included congressman-to-be Ben Nighthorse Campbell of Colorado, as well as Paul Maruyama of Colorado Springs, a Japanese language professor at the Air Force Academy whom we’ve gotten to know over the years (and who authored “Escape from Manchuria,” the real-life story of how his father helped repatriate almost two million Japanese civilians stuck in Manchuria after WWII, a book that’s since been made into a Japanese TV movie by NHK).

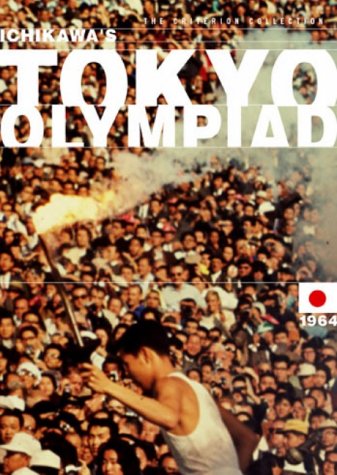

Since those games, I’ve watched and re-watched the 1965 documentary film “Tokyo Olympiad” by director Kon Ichikawa, a terrific milestone of a movie that focused on the human side of the athletes, not just the awards and competition (the Criterion Collection Blu-ray is highly recommended).

I don’t know if anyone will be shooting a documentary of this year’s Tokyo Olympiad. I hope someone does, because it promises to be one of the most unusual international sporting events of all time.

Like the rest of the world, Japan is still struggling with the Covid-19 pandemic. And its rate of vaccinations has been slow and low. Japan has been largely closed to international travel. So the government has decided the athletes and trainers can come to Japan, but no foreign spectators. No fans. No tourists. And, sadly, no families of competitors. And just this week, the government called a state of emergency in Tokyo and now not even Japanese spectators will be allowed in the new facilities that were built specifically for the Olympics.

That is true for both the Olympic Games that run July 23-August 8, and the Paralympic Games which run August 24-September 5. That means friends and families of world-class athletes competing in Tokyo will have to watch from home, not from the stands.

My heart goes out to one Denver family in particular. Robert Tanaka, a young man who has just announced he’s qualified to compete with Team USA for Judo in the Paralympics, has been training and fighting for this honor for years. His family has supported him every step of the way. Now his parents, Shelly and Rob Tanaka and his brother Nicholas, who had planned to travel with Robert to Tokyo until the games were postponed last year because of Covid, will root for him and have send along good vibes from home.

A side note about the Paralympics, which are often confused with the Special Olympics World Games. The Special Olympics are for athletes with intellectual disabilities, and is recognized by the International Olympic Committee. They were first held in 1968 and alternate summer and winter games like the Olympic Games, every other year. The Paralympic Games, governed by the International Paralympic Committee, feature athletes with a variety of physical disabilities as well as intellectual impairment. It was founded as a small competition in 1948 by British WWII veterans, and it’s held in parallel with the Olympic Games. Robert Tanaka is sight-impaired.

I hope all goes well at the Olympics and the Paralympics a couple of weeks later. I hope athletes stay safe and healthy. I hope NBC’s coverage finds ways to keep the competition exciting and compelling for viewers from around the world, even without the roar of the crowds to cheer the athletes on.

And, I wish the best of luck for Robert Tanaka and all the American athletes going to Tokyo and hoping to return with medals. Gambatte!

NOTE: This is an expanded version of a column which has been published by the Pacific Citizen, the national newspaper of the JACL — I’ve been writing columns for them for more than 20 years. I’ve scheduled interviews with Robert Tanaka and his family. Stay tuned for feature stories about his journey to Tokyo.