30 Dec Benihana founder’s son Kevin Aoki on his father’s Hall of Fame legacy

Hiroaki “Rocky” Aoki’s induction into the Asian Hall of Fame in 2023 enshrined his reputation as a giant in the history of AANHPIs, but that legacy had long been established over his long and colorful career. Rocky Aoki was a legend on many fronts.

His main claim to fame was as the founder of Benihana, the restaurant chain that began with one location in midtown Manhattan in 1964. But before Aoki turned restaurateur, he had already been a champion wrestler, starting in Japan and, after moving to the U.S. for college, he was the U.S. flyweight wrestling champion. He never lost his competitive spirit–Aoki had a passion for thrill-seeking accomplishments throughout his life, including being the first man to fly across the Pacific in a hot-air balloon (the flight ended with a crash in northern California); auto and speedboat racing (he almost died in a speedboat crash) and oh yes, a not-so-dangerous hobby, winning a world title in backgammon and hosting tournaments.

Rocky Aoki was born in 1938 in Tokyo, where his father ran a coffeeshop after World War II. His parents named the business Benihana (“red flower”)what is the , after a red safflower that his mother found growing amidst the firebombed rubble of the city. Benihana expanded into a restaurant in the Ginza shopping and dining district and began serving dishes cooked on a teppanyaki, or tabletop steel griddle that was commonly used for making okonomiyaki.

When Rocky came to the U.S. to attend college and wrestle, he earned his associate’s degree in business administration. While in school, he realized that Americans knew little about Japanese food and he could introduce them to the cuisine. But not too much of it. He decided to use the teppanyaki grills, which many Americans to this day incorrectly call a “hibachi,” which is a different type of grill that cooks over charcoal. He also famously decided that he wouldn’t force anything too slimy or fishy, and served only beef, chicken and shrimp at the start. No sushi, no raw fish. He even avoided serving miso soup, opting instead for clear soup that’s best known today as Benihana Onion Soup.

After college, Aoki saved enough money from operating an ice cream truck in Harlem to open his first Benihana. The restaurant struggled until a rave review from a New York newspaper was published. After that a host of celebrities including the likes of Muhammad Ali and the Beatles flocked to the restaurant and Aoki’s empire grew from there.

And perhaps most notably, he turned the meals at Benihana (his father was a partner in the venture) into a type of entertainment, with chefs trained to slice and dice the ingredients right on the teppanyaki top, making samurai-like sounds with the knives and spatulas, flipping eggs into their chef’s hats or tossing cooked shrimp into the mouths of diners agog from the dexterity. The chefs even sliced up onions and stacked them into a cone and turned them into a volcano by pouring oil and lighting the “mountain” on fire. Dinner at Benihana was a family-friendly affair, and a destination for special occasions. It was the gateway drug that helped make Japanese food less exotic and more mainstream Americans.

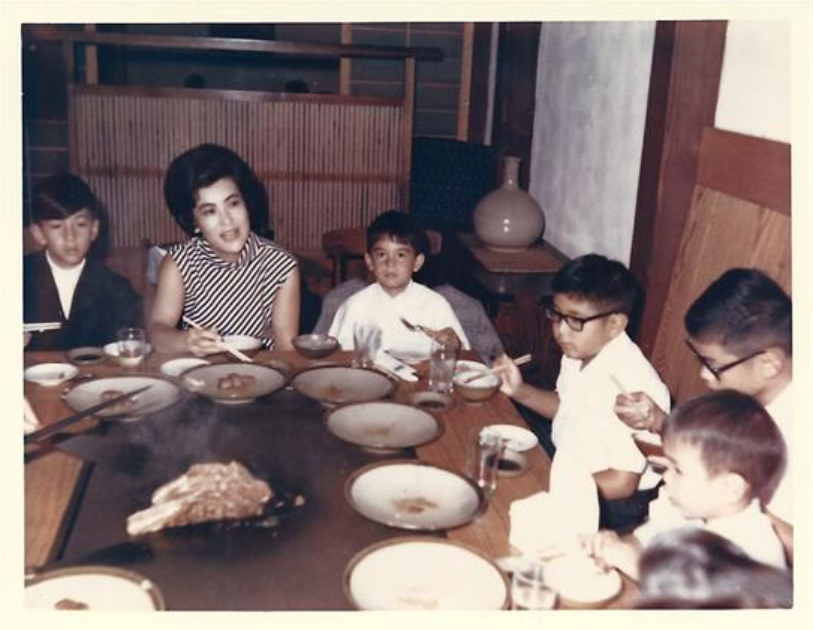

When my family moved from Japan to the U.S. in 1966, Benihana was a special family night out. When we had celebrations to mark or visitors to host, we’d head for Benihana from suburban northern Virginia to Washington, DC. The photo at the top of this blog post was taken on such a family occasion, when my mom’s childhood friend from Nemuro, Mrs. Adams, came from their New Jersey hmoe to visit us in 1968 or so. I’m the third one from the right in the white shirt, already a foodie enchanted by the treats in front of me. Our family was familiar with Japanese cuisine. But many, many families who flocked to the chain were introduced to “Nihon-shoku” — albeit a limited palette of the food — through the chefs’ playful cooking on the teppanyaki.

Aoki deserves his entree into the Asian Hall of Fame because of Benhiana’s undeniable cultural importance: the chain, which grew from his original Manhattan location to more than 100 locations around the world. Benihana made Japanese food–or at least, an Americanized introduction to it–familiar to people not just on the coasts, but in the midwest and the south.

Without Benihana, it’s hard to imagine the ubiquitous popularity of Japanese food today, with sushi (even bad sushi) available at supermarkets across America.

Aoki died in 2008 of pneumonia, but along with his driven business instincts and restless daredevil antics, he was a quixotic family man. He had seven children by three wives, and several have made names for themselves in different fields. Daughter Devon is a superstar model and actor, and son Steve is a superstar DJ who has helped make electronic dance music (EDM) a worldwide phenomenon. Steve Aoki was inducted into the Asian Hall of Fame in 2021.

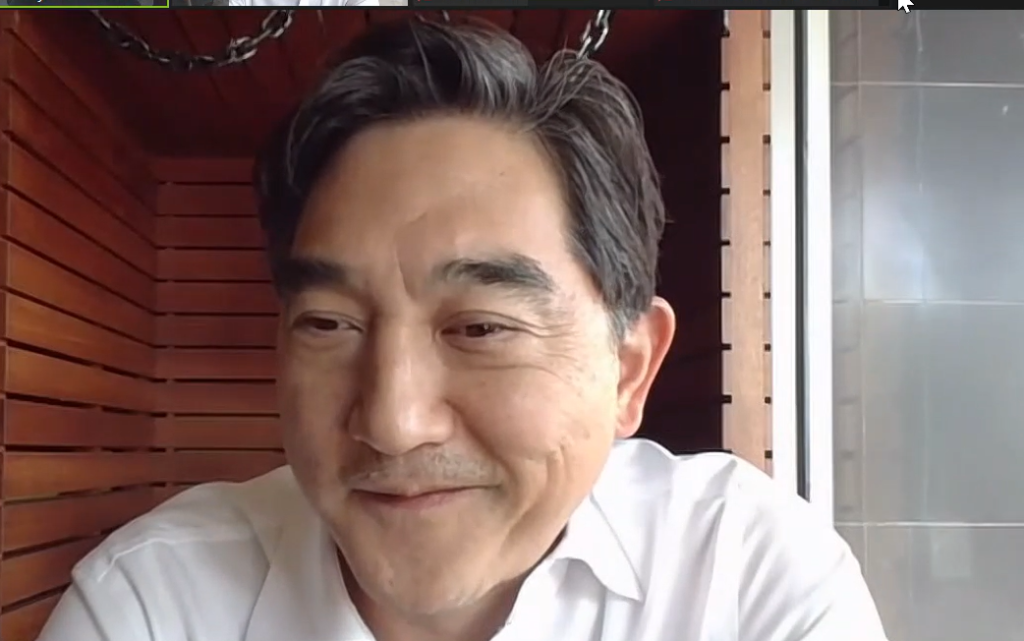

Rocky Aoki’s induction was accepted by his oldest son Kevin Aoki, who has followed in his father’s footsteps and runs the Aoki Group of 12 restaurants in Miami, Honolulu and Las Vegas. Yes, they include Aoki Teppanyaki, which carries on his father’s tradition.

I had a Zoom conversation with Kevin Aoki after the Asian Hall of Fame ceremony.

Gil Asakawa

How do you feel about your dad being in the Asian Hall of Fame?

Kevin Aoki

I feel proud as a son, knowing that my dad has achieved so much and been recognized for his achievements. I think that the Asian Hall of Fame is special because he immigrated from Japan to America. To me, my dad is kind of like the poster child of the American dream. He’s an immigrant, who came to this country with a dream with no money in his pocket and decided to make his life here.

GA

How was it for you to be there to accept his award? You usually shy away from the spotlight and work behind the scenes on your businesses.

KA

Um, I’m his oldest son. My younger brother (Steve), of course, he’s the most recognized figure of my family right now. We wanted him to go there but (he couldn’t) and you know, I would do anything for my dad or my brother.

So yeah, I felt very proud to accept this award for my dad. I brought it to my brother’s house because a lot more people come to his house, and put it on the shelf over there. And Steve is very proud too, that my dad received this award.

GA

How do you feel about the role of Benihana in the history of Japanese food in America?

KA

Yeah, it’s funny you say that because my dad’s mission when he opened his restaurant was to change the way Americans think about Japanese food. At that time in the early ‘60s, it was so foreign to them. Eating Japanese food wasn’t that appetizing. And he just took American favorites, steaks, chicken, and shrimp, put some soy sauce on there, you know, and just made it work.

I mean, it’s the craziest thing, after 60 years, teppanyaki is still a popular dish. I have a restaurant called Aoki Teppanyaki here in Hawaii and one in Miami. I have 12 restaurants and those two restaurants are the best restaurants. It’s like, it doesn’t end. The concept is still relevant. People, families love it.

GA

For you growing up in that environment, did you grow up thinking you wanted to be in the restaurant business?

KA

Yeah, I looked at my dad almost like a god figure growing up. And I, you know, when my dad started the restaurant back in 1964, I was born in 1967. We were still living in Harlem. He was just surviving, trying to make Benihana successful.

I wanted to do everything to make him proud of me. So in high school, I was a wrestler. And even in high school, I told my father, I wanna work in the restaurant. And then after college, my dad’s like, if you wanna work in one of my restaurants, you’re welcome to. I worked for him for 15 years.

After he passed away, I decided I had to open my own restaurant and survive on my own. So my dad’s never even seen any of my restaurants. I hope he’s looking down at what I’ve done and is proud of it.

GA

Do you eat at Benihana?

KA

I have my own teppanyaki restaurant, so I rarely eat at Benihana’s. If I’m with Steve, my mom, my sisters, the other siblings, we’re all together, we’ll try to book a reservation at Benihana just to commemorate my dad, just to go there and, you know, be with my dad. We do that for like Thanksgiving or Christmas.

GA

Your dad was like an adrenaline junkie?

KA

Yes, he was. I don’t think he really liked the restaurant business. I think that’s a byproduct of his business ambition, doing crazy things like flying across the ocean in a balloon and boat racing and car racing and doing everything to the limit.

GA

Do you play backgammon?

KA

I love the game. In fact, I started a backgammon club in Hawaii about five years ago and I just put it in my restaurants. So all the top backgammon players of Hawaii come to our tournament once every two weeks. And we play backgammon. I mean, it’s something that is near and dear to me because growing up with my dad, he was so busy. He didn’t have time for any of his kids, except if you’re playing backgammon with him. And you had to play for money. It could be for a dollar, or a percentage of the points. But he would not play with you unless there was a wager on the game.

Sometimes I’d get good rolls and beat the old man. Most of the time my dad beat me.

GA

How would you describe your dad’s legacy?

KA

I think his legacy is in his kids. I mean, he’s given all of us an opportunity to to be who we want to be. I think of my dad as an American dream and myself too because after my dad passed away, I just went off on my own. I started with one restaurant in Hawaii. And I take that passion that my father had and do what he did.

Note: This article Was published in an edited form in the Pacific Citizen newspaper in November, 2023.