28 Sep Can we talk? About “Miss Saigon?”

Let me say right upfront: I don’t like “Miss Saigon.”

The musical has been a megahit staple of the stage since it made its debut in London in 1989 and then Broadway in 1991. It ran for a decade in New York, and was revived in 2017. Touring versions have crisscrossed the US, including in Denver in September.

“Miss Saigon” makes lots of money for its producers and the theaters that can accommodate its huge and complex stage sets and large number of cast-members. It’s a popular musical with popular, instantly-recognizable songs.

Filipina Lea Salonga singing one of her show-stoppers from “Miss Saigon.” She auditioned when she was just 17, and debuted with the play in London. She continued the role in New York and won a Tony Award, the first Asian to earn the Broadway honor.

But, I don’t like “Miss Saigon.”

If you don’t know the show’s plot, it’s about a Việtnamese woman and a white American GI who fall in love during the last days of the Việt Nam War. They’re married, and although he plans to take her back to the US, they get separated during the fall of Sài Gòn. Chris, the soldier, doesn’t find out until three years later that Kim, the woman had a son, Tam. By then, he’s married a white woman in Atlanta and the couple travel to Việt Nam to try to establish a relationship with Kim and Tam.

Kim is devastated when she learns that Chris has married, and in the end (spoiler alert) she kills herself so that Chris and his wife Ellen would be forced to take Tam with them and raise him in America, which had been her dream since the end of the war.

It’s a pretty conventional love story, and if the specifics of the plot seem familiar, it’s because it’s a modernized version of Giacomo Puccini’s “Madama Butterfly,” the 1904 opera about a white American naval officer who marries a Japanese woman, leaves her and returns to Japan with his “real” wife, who is white. The Japanese woman, Cio Cio (“cho-cho” in Japanese means “butterfly”), also has a child, and kills herself at the end of the opera.

I don’t like “Madama Butterfly” either.

“Miss Saigon” hypnotizes its audiences with its production pomp and dramatic musical thrills, but the story is the same as a century ago, and it seems even more outrageously anachronistic and out-of-step today, in the #MeToo era, and with our heightened awareness of racial stereotypes, especially of Asians. Or maybe I’m fooling myself that Asians have finally begun to make inroads and have taken our place in the mainstream of western pop culture.

The musical is about cultural and physical imperialism, white privilege and savior complex, and unabashed misogyny and sexism, written with a condescending attitude by white people looking back at a terrible and tragic time in the history of Việt Nam. Yeah, yeah, I know it depicts “the way it was back then.” But there must be more enlightened ways to depict gut-wrenchingly offensive scenes like the opening set in a Sài Gòn whorehouse, where the allegedly biracial pimp called “The Engineer” foists prostitutes on horny American soldiers.

Did such whorehouses and prostitutes exist? Yes, undoubtedly. Did the heartbreak of bi-racial love end in separation and a tragic generation of orphans? Yes. The musical was inspired by a 1975 photograph of a woman giving up her Amerasian daughter so she could be raised in America. That image was mashed-up with the “Madama Butterfly” trope to become “Miss Saigon.”

Aside from the raw exploitation of Asian women as sexual objects, the play is traumatic for some people who lived through the war. Even as it tries to shout an anti-war message, it trivializes the militaristic Communist regime with Broadway-choreographed marching scenes, which are almost as disturbing as the whorehouse.

It’s not all awful and negative. The second act opens with “Bui Doi,” a touching number about veterans and their responsibility for leaving behind the “bụi đời,” or “dust of life,” the Amerasian children left behind by departing GIs. The song is the moral center of the production. And as I mentioned earlier, there’s a lot of powerful, memorable music throughout.

Here’s a video of “Bui Doi” from “Miss Saigon,” the moral heart of the musical.

The character of The Engineer is ultimately what completely ruins the musical for me. The character is a broad, sleazy caricature of a greedy Asian man who wants to flip off his country and is obsessed with getting to America. And, the mostly white audience loves him, laughs at him, and gives him the loudest applause as he comes out at the end of the performance.

As far as the audience is concerned, he’s the real star and point of the musical, not the star-crossed lovers or the awful horror of the war, or even the sad legacy of the bụi đời. He’s the comic relief, the jester who holds court over his women (not just in Sài Gòn but also in Thailand after the war), who just wants to live the American dream. He even humps an obscenely-sized Cadillac in one number. White British actor Jonathan Pryce was cast in this role in the original London and Broadway productions, with yellowface bronzing makeup and eyes pulled back into a sick slant. That casting almost scuttled “Miss Saigon” before it had a chance to become a big hit. At least ever since then, because of the outcry, the role has been played by Asian actors.

The plot, the stereotyping and scenes like the disgusting opening have led to protests at many productions of “Miss Saigon” that decry its racial and sexual stereotypes – available, weak and submissive Asian women and ineffectual, impotent Asian men. In one much-publicized fiasco during a Madison, Wisconsin stop of this current tour, the theater agreed to schedule a community panel discussion about the stereotype, then canceled it at the last minute, pouring fuel on the fire of protest. (It should be noted that the New York producers of the tour were all for the community panel discussion, but the theater canceled it.)

So when the Denver Center for the Performing Arts (DCPA) announced it was bringing “Miss Saigon” for a two-week run, a group of Asian American Pacific Islander community members met with DCPA management to share our concerns. To our surprise, they were open to our comments and willing to work with the community to find ways to make “Miss Saigon” a learning experience for audience members.

For starters, they published accurate portrayals of Việtnamese refugees from our community in articles written by the DCPA’s in-house journalist John Moore (a former colleague of mine from The Denver Post) from its website and “Applause” magazine (the program book).

We suggested a talk-back panel discussion with local Việtnamese community members and the DCPA countered that they could schedule an unprecedented series of talk-backs during the production, and include members of the cast and crew in addition to community members. They explained that over the decades, “Miss Saigon” has been updated to be at least as culturally accurate as possible. A wedding scene was originally sung in “ching-chong” gibberish but with the help of Vietnamese cultural consultants who are part of the cast, the song is in actual Vietnamese, and details of the props and costume are more accurate than 30 years ago.

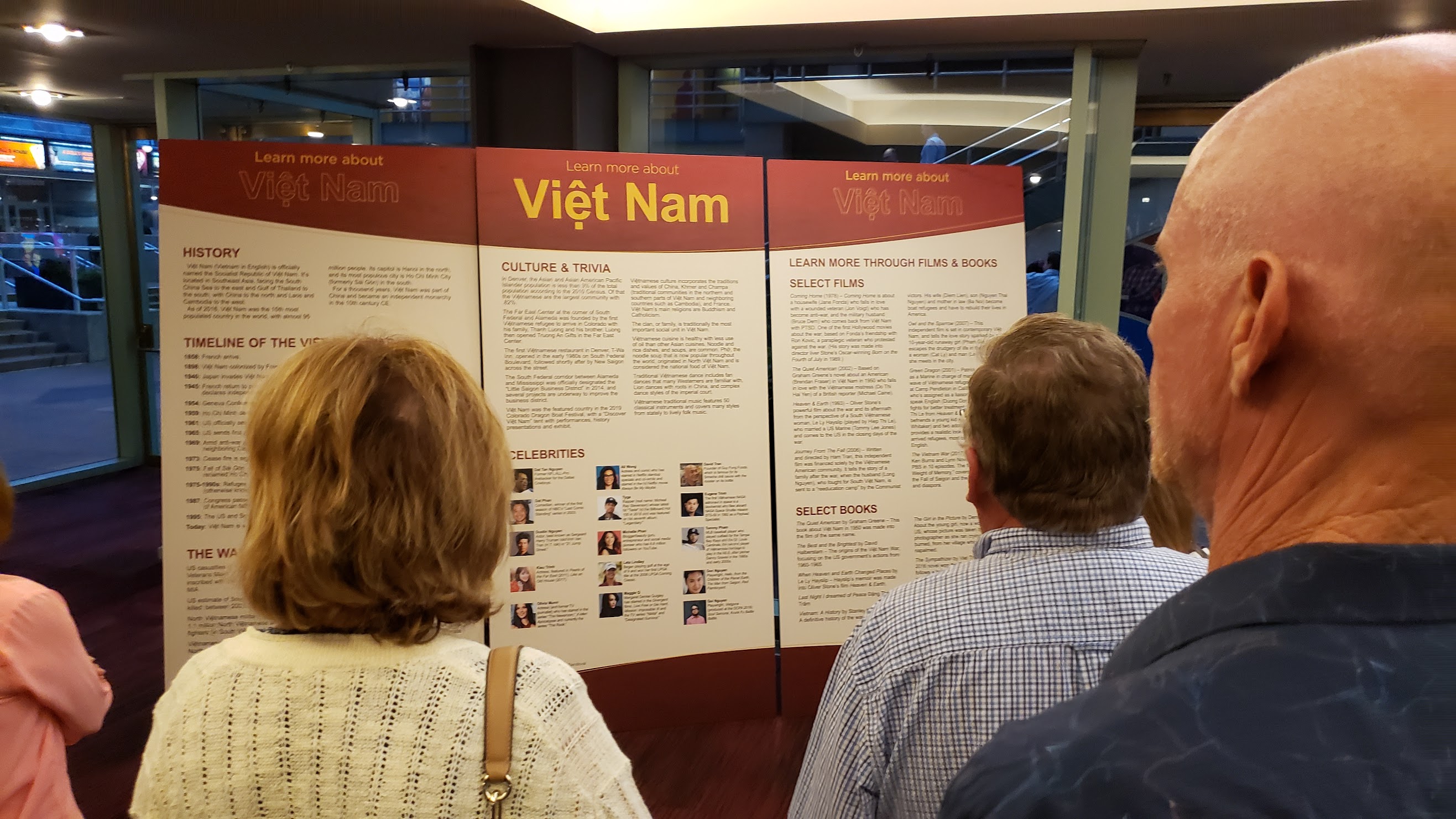

The DCPA also asked me and Nga Vuong-Sandoval, an activist for refugees whose family was part of the “boat people” wave of refugees in the post-war years, to submit statistics and research about the history of the war in Southeast Asia and its aftermath, including how many Amerasian orphans were abandoned when the US pulled out of Việt Nam. The DCPA printed these facts as well as contemporary trivia about celebrities whom you may not have known are of Việtnamese heritage, and books and movies that can tell stories other than “Miss Saigon,” on a triptych of huge poster boards (shown at the top of the article) that audience members cluster around to read before the curtain calls. (Vuong-Sandoval saw the production and later wrote about why it’s problematic for her. She wrote a moving, thoughtful essay about her reaction.)

All of the DCPA’s efforts allowed room for dialogue around the troubling issues that still pervade the production. And that, to me, is a big win – just to be able to have the conversation.

I don’t like “Miss Saigon.” But it’s unrealistic to think that we can make the musical go away and be put on a shelf to turn to dust.

In that case, I’m glad the DCPA was willing to work with Denver’s AAPI community and respect the Việtnamese community, and allow audiences and the public at large to learn more about the real-life stories of refugees and the tragic history of the war and its aftermath. I’m glad the DCPA allowed the dialogue to take place.

So, can we talk?

In fact, speaking of “Madama Butterfly,” that war-horse of the operatic canon was mounted once again in Denver earlier this summer, by Central City Opera. We had already had promising conversations with the DCPA about “Miss Saigon” so my wife Erin Yoshimura and I met with Central City Opera about our concerns over its outdated storyline. Like the DCPA, the CCO was aware of the problematic racial representations. But it’s harder in the rarified world of opera to find Asians to cast in Asian roles, so the star wasn’t. But at least there was no overt “yellowface” or eyes pulled back. And the CCO held pre-show talks with cast, crew or staff that addressed some of the issues around culturally appropriate representation.

“Butterfly” is notably different in two ways from “Saigon.” Puccini wrote the opera as a criticism of the American imperialism of the late 1800s and tosses in snarky musical references to the “Star Spangled Banner,” and its white protagonist marries Cio Cio like Chris marries Kim, but he’s portrayed as a cynical dude who never really loves her.

Here’s the official trailer for the 2019 production of Central City Opera’s “Madama Butterfly.”Erin and I were asked to participate in a CCO podcast to discuss “Madama Butterfly” with Margaret Ozaki Graves, a local Japanese American singer who wasn’t cast in “Butterfly” but served as a cultural consultant to make sure the characters and sets were as accurate as possible.

The summer of Asian representation on stage continued after we saw Central City Opera’s “Madama Butterfly,” when we got to see “Ms. Butterfly,” which turned the original opera inside-out. Produced by local Chinese American artstrepreneur Dennis Law, “Ms Butterfly” was presented as part of the Denver International Festival of Arts & Technology at the University of Denver. DU did a terrible job getting the word out, so we were among just a handful of audience members who came, curious about the opera.

Yes, it was Puccini’s music. But it was performed by a small group of Chinese musicians who played most of the orchestral parts on just a couple of high-tech instruments, and it sounded great. The cast was a full staging of the opera…. Except that the plot took place in the science fiction-future and this Butterfly was a white American woman who falls in love with a Chinese soldier who marries her and then leaves her for his Chinese wife. Like the original Puccini Cio Cio, she has a child by him, and kills herself in the end.

Here’s a KMGH TV report about “Ms Butterfly.”As an Asian American, I found this plot turnaround somewhat satisfying but the misogynist narrative still troubling. I wish more people had seen it, so we could have some dialogue and discussion about both versions of “Butterfly,” and about “Miss Saigon.”

Talking about these stories and the issues the represent might lead to better understanding, and help build a bridge over the racial divide that’s tearing our country apart.

So once again, can we talk?

One thing I don’t need to talk about is how much I hate “The Mikado,” I which find so racially offensive that it’s irredeemable. Like the people who think “Saigon” should never be mounted again, I wish “Mikado” could be shelved once and for all.

If you don’t know it, it’s a “comic opera” by Gilbert and Sullivan that premiered in 1885 that takes place in a Japanese town of “Titipu.” It was written only two decades after Japan was opened up by American warships in Tokyo Bay, and Westerners had exotic fantasies about the country. The French impressionists absorbed Japan’s art, but Gilbert and Sullivan, who never bothered to learn anything real about Japan, simply set a bunch of ludicrous characters in a made-up town, allegedly as a criticism of English aristocracy (at Japan’s expense).

It’s a ridiculous, disgusting and outdated piece of theatrical trash. And I saw it at the University of Denver’s Newman Center, where Dennis Law debuted “Ms Butterfly.” Shame on them. If they ever try to bring it back, I’ll want to meet with them in advance to try and place some sort of context around the production in a way that makes sense of the opera and educate audiences about its stupidity.

Do you think they’ll want to talk?

Here are links to John Moore’s excellent interview profiles of Vietnamese and Asian American community (and cast members) that were done to give more context to “Miss Saigon”:

Nga Vuong-Sandoval

Tri Ma

Joie N Le

Rae Lee Case