02 Dec Asian representation: It’s getting better, but still has ages-old challenges

Note: An edited version of this post will run in the Holiday Issue of the national JACL‘s Pacific Citizen newspaper.

Japanese Americans and the wider Asian Americans and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities are seeing more of ourselves reflected in pop culture these days, but the high arts has a ways to go. It’s important to recognize the ongoing challenges of representation, because they affect our view of ourselves and our community.

The past year-and-a-half has seen a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes across the United States, thanks to fanning of the racism sparked the covid-19 pandemic. And yet, Asians have become more and more a part of the American cultural fabric. Through arts and entertainment (and yeah, food), stereotypes, ignorance and long-held animus can be called out, confronted and hopefully, discussed so that solutions to the historical hate can be found for the future.

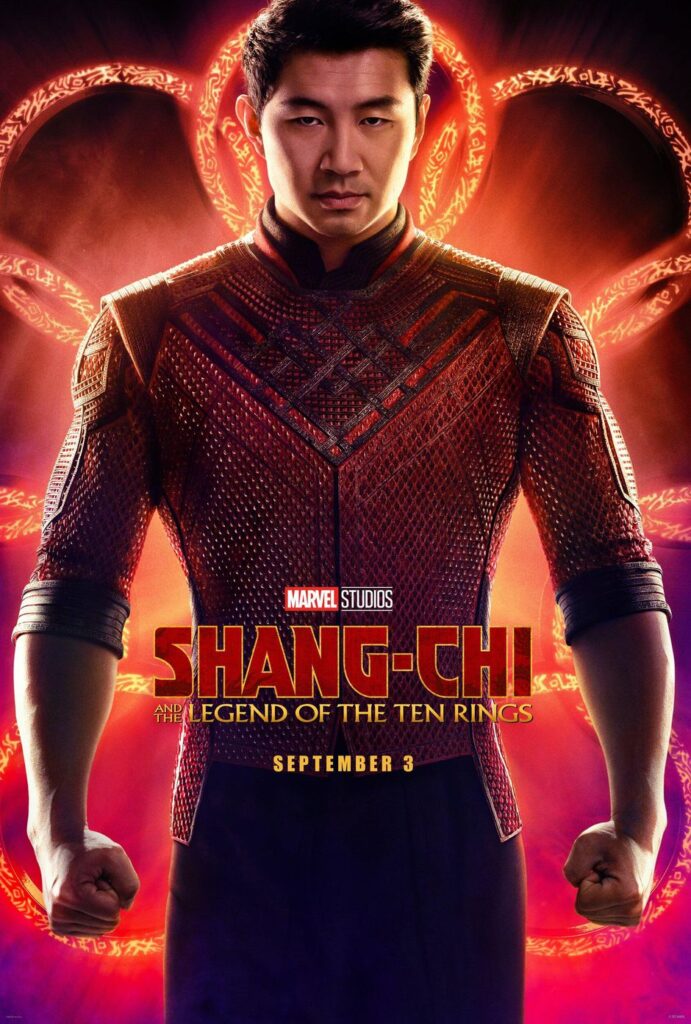

Pop culture has definitely embraced Asians as a part of American society, with productions that were started in motion long before even the arrival of covid. “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings” has introduced audiences this fall to a hunky Asian American Pacific Islander superhero with Simu Liu in the starring role, but the movie wasn’t produced in the pandemic bubble, or as a reaction to the anti-Asian attacks. Marvel’s Asian superhero movie was green-lit in 2001 and went into serious production in 2019.

The timing this year was perfect: Having a butt-kicking AAPI superhero and a wise-cracking sidekick in Awkwafina taking over the box-office totals for a full month and succeeding as a streaming hit gave some hope that things may be changing for Asians in America. The recent addition of Ji-Young, the first-ever Asian American Muppet character on “Sesame Street” boosted this feeling of cultural arrival.

Sure, there are lots more Asians working in pop culture now in television shows and movies and even commercials that represent more opportunities for our faces to be part of “mainstream” America.

But we can look at other arts and see long-held stereotypes and racist tropes still on display – and considered classics, no less. The Broadway musical theater world still loves “Miss Saigon” despite its racist and misogynist story about a Vietnamese woman who falls in love with an American GI.

And, that story is just the modernized version of “Madama Butterfly,” Puccini’s celebrated 1904 opera about a Japanese woman who falls in love with an American soldier stationed in Japan. It doesn’t require a spoiler alert to say that in both the opera and musical, the woman has a baby after the soldier leaves her, and when he comes back some years later with his American wife, the woman commits suicide.

“Madama Butterfly” is one of the giants of the opera canon – it’s a classic that’s cited for its drama and music. It’s also noted for its biting criticism of American imperialism, which is a subtext that isn’t focused on much these days. But the opera does catch flak for its outdated portrayal of Japanese culture and exotification of Japanese women. When Central City Opera performed it two years ago, my wife and I met with opera management and shared our concerns. We were invited to discuss “Madama Butterfly” in a CCO podcast and the cast and crew added pre-show talks about the problematic portrayals and representations.

The Boston Lyric Opera (BLO) had planned to raise the curtain on “Madama Butterfly” for the fall 2021 season, but amidst the headlines about anti-Asian hate, BLO’s management and its cast and crew earlier decided not to perform it. Instead, they’ve launched “The Butterfly Process,” a series of public discussions and community events to “reexamine the history and legacy of this opera” and find ways to acknowledge its artistic legacy without continuing its racial legacy. The BLO asked Phil Chan, a dancer and choreographer who in 2017 co-founded “Final Bow for Yellowface,” with his partner, Georgina Pazcoguin, for help and guidance. “Final Bow for Yellowface” was launched because of the number in Tchaikovsky’s “The Nutcracker” – yes, the seasonal classical favorite – that features a “Chinese” dance that was too often performed as a racial caricature, and with white dancers in yellowface.

Chan has a reputation as a creative who brings a multicultural perspective to even the canon of classical “high arts” – meaning European, white-centered arts. So BLO contacted him for his help with “Butterfly.”

He’s not the only one, or the first person to push for AAPIs in the arts. “There’s the Coalition for Asian Pacifics in Entertainment, who’ve been doing having this conversation and leading it in Hollywood already for, you know, 40-50 years already,” he said in an interview.

But the lack of appropriate Asian representation in dance pushed him to help launch “Final Bow for Yellowface.” “It’s, it’s, you know, what is my tiny corner of the world? And where can I make a difference?

So he started with dance, aiming at “Nutcracker,” and every holiday season as symphonies across the country drag out the chestnut, he and his partner get media coverage. But, he added, “I’m an opera queen, a self-professed opera queen,” so he’s now hoping to get the same attention for “Butterfly.” He’s working with a new organization, the Asian Opera Alliance, and hopes it can have some impact on an artform that is decidedly Eurocentric, in both its canon and its name-brand performers.

“I think the reason why BLO came to me was because sort of my niche is figuring out how do we take traditional Eurocentric works, and expand them for a multiracial audience,” Chan said. “So there’s a lot of really good pieces of art that come from Europe, but it has a strictly European view of the world. It was made by white people, for white people, paid for by white people – paid for often by the Tsar or the king. And that doesn’t always work with when you have a multiracial community that you’re playing for today.”

He cautioned that he’s not pushing for cancel culture. “I’m not saying that any white artists from Europe is inherently a colonialist, anything they made from Europe ever needs to not be performed anymore in order to make room for, you know, voices of color. That’s not how it works. In reality, like, yes, that would be lovely.

“But that’s like, if you’re trying to turn, you know, change directions in a car, and you’re going 300 miles an hour. Yeah, you can do a really sharp turn but your car will flip. You have to turn slowly to keep yourself moving.

“And looking at works like Butterfly and like Nutcracker, yeah, they’re kind of colonialist, you could say that, but they also bring in enough money so that these opera companies can commission new works by people of color. So it’s sort of we’re using them to bring equity.”

He’s not ignoring the wave of anti-Asian sentiment that has flourished in the current divided country, either. “I mean, I’ve been spat on multiple times during the pandemic. I was assaulted in an elevator a couple weeks ago. My co-founder was spat on just yesterday. This is the climate we’re in and I’m looking to the future. I’m looking at the way that we’ve already demonized, you know, Asian Americans, Kung Flu, China flu, you know, spitting on people, the hysteria around attacking Asian people,” he warned.

“And I’m seeing it’s not far off from putting people like us in camps, again, it’s happened before and we can do it again. And where we’re seeing this ugly side of the American experience come out, where there just might be enough fear and resentment for you to say, you know, maybe I wouldn’t feel so bad if someone just rounded up my neighbor.”

When he met with the Asian Opera Alliance on Zoom, he said the people on the call had all performed in “Butterfly,” and many worked together in the same productions.

“So we talked about the issues around ‘Butterfly,’ we talked about what are the issues on stage, you know, everything from Japanese stuff to bad artistic choices that directors have made, microaggressions like white directors telling them how to act more Japanese when they are of Japanese descent. And then how butterfly both makes a career for Asian singers sustains a career for Asian singers, but also pigeonholes them into only singing ‘Turandot’ and ‘Butterfly.’”

That AOA meeting set the stage for the current process. “So what do these opera companies do in the larger ecosystem? Those are the questions that came out of that conversation. And I think BLO realized that they couldn’t ever stage butterfly, again, without going this deep without really asking some of these questions.”

The Butterfly Process will start Dec. 14 with a free online discussion about the history of “Butterfly” and its impact through WWII (performances were cancelled after the war because people thought the opera was pro Japanese). The conversation will be between Chan and Dr. Kunio Hara, a Japanese-born professor of music history and an expert on Puccini and Orientalism in music.

Ultimately, Chan sees a path for diversity in the arts by upending expectations and ignoring typecasting.

“Oh, if the person is Japanese do you have to find a Japanese or Japanese-presenting person?” he asked. “Or do you go for colorblind casting where anybody can sing any role as long as the voice fits? So what is the best strategy? How do you do it? So chewing on those things with artists, directors, scholars, singers, you know, folks who are in the field who are doing this work, who have skin in the game, but really centering the Asian experience.”

He credits “Hamilton” with showing Broadway – and the world – that you can have a multicultural cast in a traditional setting and not just tell an old story with a new point of view , but to add new layers of humanity to characters that audiences thought they already knew.

“Yeah, shifting to a multiracial way of treating history shows us nuance, shows us new ways and new perspectives to history, which is so important,” he said. He suggested a modern way of staging the racist Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera “The Mikado,” a satire about English aristocracy which takes place in a fictional Japanese town called “Titipu” and has always featured white actors in yellowface and phony kimono since the late 1800s. He’s a fan of the play but realizes its racial stereotypes are a problem.

“I will tell you, it’s literally best music, it is the best dialogue. It is so fucking funny,” he said, laughing. “And the problem is lazy white directors who think it’s about Japanese people. It’s not. It’s about England. So what I would do, is an all-Asian cast in white face. And my premise would be, it would be as if a kabuki theater had never heard of England. And they wanted to do this. This British opera called ‘The Mikado’ about England. But we don’t quite know what they look like. So I guess maybe like, they would wear tartan kimonos, you know? They put like forks and spoons in their hair like chopsticks, and have like Big Ben in the background with a pagoda on it. Just like I you know, as if someone were to describe a fantasy Victorian to a Japanese person who just like literally could not even imagine what England looked like. And it would be an all Asian cast, pretending to be British people.”

It would be wonderful if Chan gets the chance to mount “The Mikado” this way – we’d certainly go see it! But these issues aren’t all funny, and Chan notes the reason why it’s important to bring the lens of diversity to the “classic” works of art.

“My grandfather lived through, you know, the ugliest time in China. And he would have been horrified that my dance partner for many years was a Japanese ballerina, like, the fact that I was touching a Japanese person would have just repulsed him,” Chan said. “And the fact that I’m doing this work now, would have just been so confusing to him. But I think that, like, you know, just like, even in my own family, how far we can come to turn a deep hatred into a shared love and a shared empathy.

“Yes, I am not Japanese. But I care about this issue. Because, yeah, me and my family could be in a camp too. And this is, and this is also my history as an Asian American, even though I’m not Japanese. It is part of my history that has to stay alive.”

That’s the spirit of community that we all need to celebrate this season, and all year. Happy Holidays, everyone!

Jan. 2, 2022: Happy New Year, everyone! I just came across this Nikkei View post I wrote in 2015, and it’s like a prequel to the above article, focusing on AAPI representAsian in TV shows.