09 Jul Acknowledging inspirations: how I became a music critic

My family moved from Japan to the Washington DC area in 1966 when I was eight years old, and I fell in love with American ways and U.S. pop culture. I like to joke that I learned every American cuss word and forgot most of my Japanese in three weeks.

One of the things I embraced wholeheartedly was American pop music—specifically, Top 40 music on AM radio stations that played hit after hit. I loved the energy of the fast-talking DJs, the commercials for everything from fast food to car dealerships, even the melodious jingles (“WPGC, good guy radio,” “More music! WEAM!” or the always popular “The hits just keep on comin’!”) and of course, the music.

The mid-Sixties was the golden era (sorry, young folks, I have to geek out on “OK Boomer” memories here) of the kind of catchy hit songs that appealed to everyone, everywhere, at the same time. “The Sound of Young America,” Motown’s tagline, said it all: the music of the rock and roll era was rooted in R&B and soul, but the hits that appealed to an entire generation included British Invasion groups like the Beatles and Stones, folk music, folk-rock, country and a zillion goofy novelty songs (think “Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini,” a 1960 hit still in rotation in 1966 as a summertime “Golden Oldie”). I vividly remember riding to elementary school in the yellow school bus with all the kids singing “we all live in a Yellow Submarine.”

But the sounds of music also included the early rumblings of protest and counterculture perspectives. The young people who’d become tagged as “hippies” were not just tuned in, but getting turned on with drugs and sex, and a movement was gathering in San Francisco. Songs like the 1967 hit “San Franciscan Night” by the British band the Animals and another the same year, Scott Mackenzie’s “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)” accompanied the Monterey Pop Music Festival held during that “Summer of Love” south of San Francisco.

Monterey Pop featured an eye- and ear-opening mix of Top 40 hitmakers that appealed to all ages (Mamas and Papas, Association, the Byrds at a tipping point between pop and rock), as well as a fresh generation of artists that heralded a new, hipper kind of music that rocked harder, was bluesier, or ethnic, had lyrics about social issues and politics (Janis Joplin with Big Brother and the Holding Company, Ravi Shankar, Hugh Masekela, Simon and Garfunkel, Jimi Hendrix and lots more).

One other sign that the times were a-changin’ was the launch of a new magazine (originally on newsprint, more like a newspaper) called Rolling Stone, which was headquartered in San Francisco, of course. It had stories about music first and foremost with reviews and feature stories galore, but it also covered the emerging counterculture and put the social evolution of the country into a larger context than mere pop culture.

By the time I started reading RS in the early 1970s as a teenager, it was a monthly bible for my young, impressionable mind. There were names in the magazine’s masthead that I always noticed. The first was Cameron Crowe, a writer who seemed to share the same musical tastes as me. His first cover story for RS in 1973 was about the Allman Brothers Band, and he wrote cover stories about Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, Eagles – all icons of mine at the time. Then I found out he was just a couple of months older than me and that made me so jealous that I decided that dammit, if he can be a rock critic, so can I. I started writing reviews for my high school newspaper.

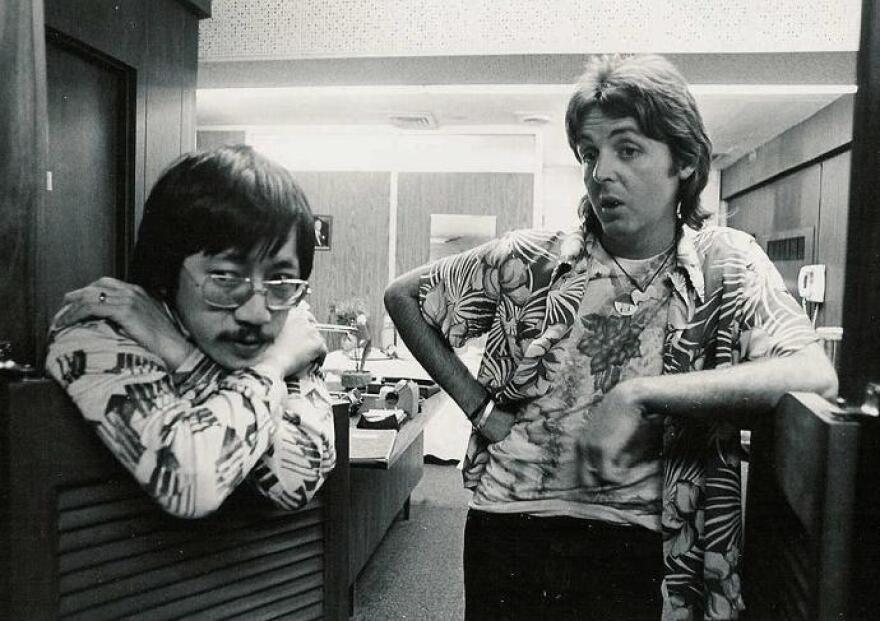

The second inspiration was Ben Fong-Torres. I knew from the name and photos that he was Asian American. He began writing for RS in 1968, was named news editor in 1969, and became the magazine’s first music editor, and later senior editor through the 1970s. I read dozens of stories by Fong-Torres. I also read his books about music—“Hickory Wind” about country rock pioneer Gram Parsons, and “The Hits Just Keep on Coming,” a must-read history of Top-40 radio—as well as an autobiography, “The Rice Room,” about growing up in Oakland with his parents who ran a Chinese restaurant. The world learned from the fictionalized biographical film “Almost Famous” in 2000 by the adult Cameron Crowe, that Fong-Torres hired Crowe to write for RS as a teenager. Two of my inspirations overlapped!

Fong-Torres, who’s now 75, has written for a variety of magazines since leaving RS, and has become a fixture of San Francisco’s music scene with a radio show (he was a DJ on the legendary KSAN during the 1970s), and a host for the TV broadcast of the annual San Francisco Chinese New Year’s Parade, for which he’s won five Emmy Awards.

I got to meet Fong-Torres once when I was visiting San Francisco. We sat in a tech company office where he worked at the time, and I expressed my gratitude to him for being one of my inspirations. He was gracious and appreciative. Having Asian Americans in the media is important—he made an impact on me simply by having his name in one of my favorite publications. I’ve learned that my early writing for Denver’s alternative weekly newspaper, Westword, was noticed by Asians, even older readers who could care less about rock music or anything else I wrote about, simply because of my name.

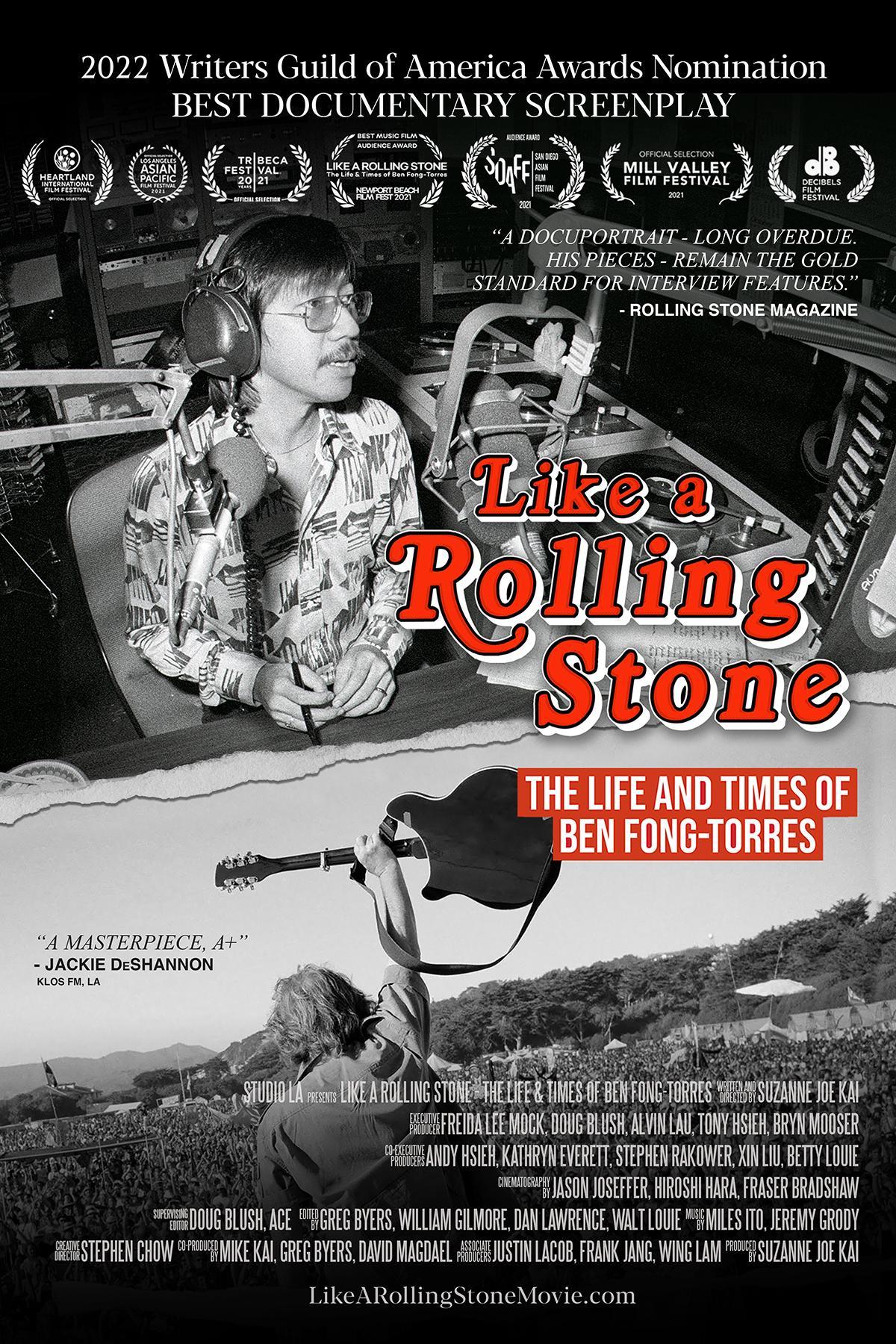

And now, filmmaker Suzanne Joe Kai has finished a project she started in 2010, “Like a Rolling Stone: The Life and Times of Ben Fong-Torres,” which is a comprehensive documentary about Fong-Torres’ long, strange trip from young music fan to an elder statesman for his community. It made the rounds of film festivals and is now available to view on Netflix.

The film does a great job of weaving his family and personal life through the fabric of his amazing career, and Kai got backstage access following Fong-Torres at shows like Elton John, where he’s warmly greeted by the superstar. The film also shows how much he’s loved by a range of musicians from Ray Manzarek of the Doors to Carlos Santana. Kai captures Fong-Torres’ meticulous archiving of his journalism, with recordings of every interview he’s ever done preserved in file cabinets in his home office. She includes fascinating clips of his interviews (Stevie Wonder! Marvin Gaye!) into the documentary.

Kai puts Fong-Torres’ life into a larger cultural context, starting with the anti-Chinese mood in the U.S. in the 1800s and through his family’s arrival and his father’s challenges in the restaurant industry. The film also explains Fong-Torres’ name: it was a way to get around the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, by buying an identity and passport as a citizen of the Philippines, a country from which emigrants to the U.S. were allowed.

The film is rich with insights and leads to an even greater appreciation for Fong-Torres’ life (including the tragic murder of his brother) and storied career. But one of my favorite scenes is when Fong-Torres reminisces about his own early inspiration and why he fell in love with Top-40 radio as a kid. He recalls Bay Area radio jock Gary Owens (who later went on to a spot on the hit TV show “Laugh-In”) and credits Owens for his love of radio even to this day, mimicking Owen’s deep resonant voice.

“Like a Rolling Stone” is required viewing for anyone who loves pop music and rock and roll, and classic radio (both the lively AM years and the low-key, hippiefied FM era), and of course, Rolling Stone magazine.

Watching the documentary, I was reminded why I became a music critic and chose writing for my career. Thanks, Ben! And thanks, Suzanne!

Note: An edited version of this post will be published on the Pacific Citizen, the national newspaper of the JACL.