September 12, 2009

NOTE to visitors who may have come across this 2009 blog post from a 2019 New York Times article by Nina Ichikawa, "Looking for a Gold-Rush Town Named Chinese Camp," which links to my old blog post because the writer saw the wonton font on a building in northern California, I was surprised to see the bump in traffic from the link. So I updated the piece and re-posted it on my newer Nikkei View blog. Thanks for visiting, and please check out the new site. - Gil Asakawa

Can a font express a racial stereotype?

I know I'm climbing on my soap box and risking being called over-sensitive and too p.c. But when I noticed a promo on Facebook this morning for the Asia Food Fest in Austin, Texas, and saw the logo for the event, my stomach clenched just a little bit. The words were spelled out in the "Wonton" font, the curvy, pointy -- shall I say, "slanty" -- lettering that I associate with a lifetime of Asian racial caricatures.

I hate it when non-Asians use it as a way of appearing "Asian," and I'm disappointed when Asians use it thinking that non-Asians will identify with it. Austin's Asia Food Fest, which I'm sure is a wonderful event, is organized by the Texas Asian Chamber of Commerce, Texas Culinary Academy, and SATAY Restaurant (one of my favorite restaurants anywhere, and one I visited every year for a decade when I attended the South By Southwest music festival), so it's not a phony, faux-Asian affair. Here's how the Fest was started, from its About page:

Dr. Foo Swasdee, owner of SATAY Restaurant, founded the ASIA Food Fest in 2006 to educate people about Asian ingredients, food, and cooking. As Austin Asian population grows (doubling every 10 years), the more choices Austin Asian Food Lovers have to choose from!

But the logo still bummed me out, so I tried to reason my reaction out internally.

When I see the font, I hear the words spoken in my head in the sing-songy "ching chong" sound that I grew up hearing in racist chants, like when white kids taunted me in school, and told me to "go home" or "go back to China" (they never said go back to Japan, which would actually have been correct, since I was born in Tokyo).

I think of words in anti-Asian or anti-Japanese signs. I see Wonton and I see the words "Jap," "Nip," "Chink," "gook," "slope." I can't help it. In my experience, the font has been associated too often with racism aimed at me.

I think of words in anti-Asian or anti-Japanese signs. I see Wonton and I see the words "Jap," "Nip," "Chink," "gook," "slope." I can't help it. In my experience, the font has been associated too often with racism aimed at me.

Which is not to say it's always racist. Wonton's used all over the place, and a lot of times I zone it out. Chinese takeout boxes often have something written in the font. Many Asian restaurants (with old signs and menus) still use it. But then some old-timer Asian groceries still say 'Oriental" too. We allow for that, but as we move forward we expect those uses to fade.

Times change, right?

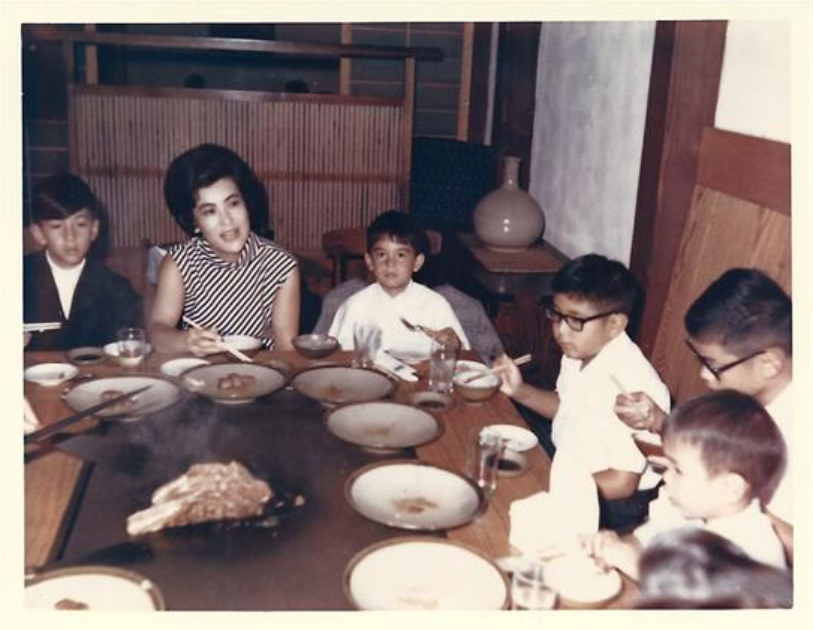

Hiroshi Watanabe as Jimmy and Nae as his sister Aiko in director Dave Boyle's independent film "White on Rice."

Erin and I attended a screening tonight of a new movie, "White on Rice," sponsored by Denver's Asian Avenue Magazine at the Starz Film Center, and thoroughly enjoyed the film. It's a sweet romantic comedy about an affable doofus of a Japanese man, 40-year-old Hajime "Jimmy" Beppu, who leaves Japan when his wife divorces him, and moves in with his sister and her husband and son in America. A hapless loser, Jimmy's reduced (when he's not living in a park or in his company's broom closet) to sharing his young nephew's bunk bed and pining after his brother-in-law's niece Ramona, who also moves in with the family.

"White on Rice" pokes gentle fun at Japanese cultural values and personalities (the gruff, the clowny, the servile) but does it with respect, never lowering itself down to parody or worse, stereotype.

The movie's chockfull of Asian Americans in addition to the rich portrayals of the Japanese characters: Jimmy's employer,a customer service company, has several Asian Americans, including Jimmy's friend Tim, played by James Kyson Lee of "Heroes" fame, who ends up being Ramona's love interest, thwarting Jimmy's obsession. The ensemble cast, which includes Hiroshi Watanabe as Jimmy, Japanese actress Nae as Jimmy's sister Aiko, Mio Takada as Aiko's husband, Lynn Chen (viewers may recognize her from "Saving Face") as Ramona, and very young Justin Kwong as the strange and wonderfully straight-faced kid Bob.

The cast is mostly Asian and Asian American. Almost half the dialogue is in Japanese with subtitles. And, the co-writer and director, Dave Boyle, is a 27-year-old Mormon Caucasian from Provo, Utah.

"Yeah, that's always the first question people ask," he said tonight after the screening. "So, what's with the white guy making a movie about Asians?"

Hiroshi Watanabe as Jimmy and Nae as his sister Aiko in director Dave Boyle's independent film "White on Rice."

Erin and I attended a screening tonight of a new movie, "White on Rice," sponsored by Denver's Asian Avenue Magazine at the Starz Film Center, and thoroughly enjoyed the film. It's a sweet romantic comedy about an affable doofus of a Japanese man, 40-year-old Hajime "Jimmy" Beppu, who leaves Japan when his wife divorces him, and moves in with his sister and her husband and son in America. A hapless loser, Jimmy's reduced (when he's not living in a park or in his company's broom closet) to sharing his young nephew's bunk bed and pining after his brother-in-law's niece Ramona, who also moves in with the family.

"White on Rice" pokes gentle fun at Japanese cultural values and personalities (the gruff, the clowny, the servile) but does it with respect, never lowering itself down to parody or worse, stereotype.

The movie's chockfull of Asian Americans in addition to the rich portrayals of the Japanese characters: Jimmy's employer,a customer service company, has several Asian Americans, including Jimmy's friend Tim, played by James Kyson Lee of "Heroes" fame, who ends up being Ramona's love interest, thwarting Jimmy's obsession. The ensemble cast, which includes Hiroshi Watanabe as Jimmy, Japanese actress Nae as Jimmy's sister Aiko, Mio Takada as Aiko's husband, Lynn Chen (viewers may recognize her from "Saving Face") as Ramona, and very young Justin Kwong as the strange and wonderfully straight-faced kid Bob.

The cast is mostly Asian and Asian American. Almost half the dialogue is in Japanese with subtitles. And, the co-writer and director, Dave Boyle, is a 27-year-old Mormon Caucasian from Provo, Utah.

"Yeah, that's always the first question people ask," he said tonight after the screening. "So, what's with the white guy making a movie about Asians?"

Note that I said Asian Americans, not Asians. The great thing about Kylie and the new faces of Asian American Pacific Islanders on the small screen is that they have my face, and my voice -- which is to say, they don't have accents and clearly aren't foreigners.

I should add here that I have nothing against recent immigrants and first-generation Asian Americans. They are the rich soil in which our identity is deeply rooted, and whether you're Japanese American, Korean American, Chinese American, Vietnamese American, Cambodian, Indian, Thai, Laotian, Hmong, whatever, we owe the immigrants who endured hardships to leave their country to start new lives in the U.S. a salute of thanks for making it possible for us to be who we are today. We're the sum total of our ethnic cultural values and the freedom and experience of growing up in America.

Anyway, my point: My fellow AAPI bloggers have been pointing out how many Asian Americans are showing up in TV shows in roles where they don't have to act as foreigners, but are allowed to be Americans of Asian heritage. And those heritages don't even have to be part of the plot.

Sure, there are still roles that cast Asian Americans as foreigners.

"

Note that I said Asian Americans, not Asians. The great thing about Kylie and the new faces of Asian American Pacific Islanders on the small screen is that they have my face, and my voice -- which is to say, they don't have accents and clearly aren't foreigners.

I should add here that I have nothing against recent immigrants and first-generation Asian Americans. They are the rich soil in which our identity is deeply rooted, and whether you're Japanese American, Korean American, Chinese American, Vietnamese American, Cambodian, Indian, Thai, Laotian, Hmong, whatever, we owe the immigrants who endured hardships to leave their country to start new lives in the U.S. a salute of thanks for making it possible for us to be who we are today. We're the sum total of our ethnic cultural values and the freedom and experience of growing up in America.

Anyway, my point: My fellow AAPI bloggers have been pointing out how many Asian Americans are showing up in TV shows in roles where they don't have to act as foreigners, but are allowed to be Americans of Asian heritage. And those heritages don't even have to be part of the plot.

Sure, there are still roles that cast Asian Americans as foreigners.

" I've seen emails criss-crossing the Internet, and a couple of blogs mentioning this, but I just got an email directly from UT-Texas asking for help, so I thought I should post about this. Dr. Eun-Ok Im (left), an internationally known expert in cross-cultural women’s health issues at the University of Texas at Austin, needs subjects for a health study -- and you don't need to live in Austin to participate.

Dr. Im is conducting an Internet study on the physical activity attitudes among diverse ethnic groups of middle-aged women (40-60 Y/O). She needs Asian American women to sign up so that her study can provide a more complete data sample. "Furthermore, Asian American women’s opinions and experiences are very imperative," the email asking for help notes, "and cannot be neglected because the Asian American population is expanding very quickly in America."

Interested women can click to the

I've seen emails criss-crossing the Internet, and a couple of blogs mentioning this, but I just got an email directly from UT-Texas asking for help, so I thought I should post about this. Dr. Eun-Ok Im (left), an internationally known expert in cross-cultural women’s health issues at the University of Texas at Austin, needs subjects for a health study -- and you don't need to live in Austin to participate.

Dr. Im is conducting an Internet study on the physical activity attitudes among diverse ethnic groups of middle-aged women (40-60 Y/O). She needs Asian American women to sign up so that her study can provide a more complete data sample. "Furthermore, Asian American women’s opinions and experiences are very imperative," the email asking for help notes, "and cannot be neglected because the Asian American population is expanding very quickly in America."

Interested women can click to the  Erin and I have always been wistfully jealous of our friends in Los Angeles and San Francisco, for lots of reasons but not least the fact that they can eat killer

Erin and I have always been wistfully jealous of our friends in Los Angeles and San Francisco, for lots of reasons but not least the fact that they can eat killer  I realize that when I point out how something as seemingly benign as the "won ton" font bugs me, readers might think I'm being petty and overly sensitive. But I hope those readers will respect my opinion if something does piss me off. Plus, I hope everyone can understand why certain things are just plain offensive to Asian Americans, not as a result of over-sensitivity but simply because they're racist stereotypes.

One of them is the "ching-chong' accent that comes out of the

I realize that when I point out how something as seemingly benign as the "won ton" font bugs me, readers might think I'm being petty and overly sensitive. But I hope those readers will respect my opinion if something does piss me off. Plus, I hope everyone can understand why certain things are just plain offensive to Asian Americans, not as a result of over-sensitivity but simply because they're racist stereotypes.

One of them is the "ching-chong' accent that comes out of the  Racist caricatures of Japanese were common during World War II, with even Bugs Bunny getting into the act in a cartoon, and a young Theodore Geisel --

Racist caricatures of Japanese were common during World War II, with even Bugs Bunny getting into the act in a cartoon, and a young Theodore Geisel --  Another was the proliferation and propagation of racist stereotypes.

One incredible example is a training booklet published by the U.S. Army titled "

Another was the proliferation and propagation of racist stereotypes.

One incredible example is a training booklet published by the U.S. Army titled "

I think of words in anti-Asian or anti-Japanese signs. I see Wonton and I see the words "Jap," "Nip," "Chink," "gook," "slope." I can't help it. In my experience, the font has been associated too often with racism aimed at me.

I think of words in anti-Asian or anti-Japanese signs. I see Wonton and I see the words "Jap," "Nip," "Chink," "gook," "slope." I can't help it. In my experience, the font has been associated too often with racism aimed at me. Erin and I are taking September off from doing interviews for

Erin and I are taking September off from doing interviews for