Note: This post was originally published on AARP’s AAPI Community Facebook page.

“The Martian” starring Matt Damon as an astronaut stranded on the Red Planet curiously won the Golden Globe Award in December as the best musical or comedy (hint: it’s really not either, though there’s some funny lines) but on Oscar night, despite being nominated for six awards; the Academy Awards left the movie stranded.

“The Martian” starring Matt Damon as an astronaut stranded on the Red Planet curiously won the Golden Globe Award in December as the best musical or comedy (hint: it’s really not either, though there’s some funny lines) but on Oscar night, despite being nominated for six awards; the Academy Awards left the movie stranded.

The lack of awards hasn’t hurt the film, which is also now available on DVD, Blu-Ray and streaming services. It’s a commercial hit.

But it took some critical hits when it was originally released in 2015, because two of its characters, who were Asian American in the bestselling book by Andy Weir, were played by Caucasian and African American actors on the big screen.

The switch was called “whitewashing” by Asian American groups who accused director Ridley Scott of depriving Asian American actors of significant roles. Both characters kept their Asian names from the book – one NASA scientist is named “Park” and her background is never explained while the other is named “Kapoor” and is explained in the film as half black and half South Asian.

The lack of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Hollywood is an old complaint, and especially in the science fiction genre. George Takei’s “Sulu” in the 1960s Star Trek series and subsequent films is a big exception. As an example, the “Star Wars” franchise features scant few Asian faces (unless they’re ugly aliens who dress and sound vaguely Asian). It’s as if in the future, Asians just never make it into space.

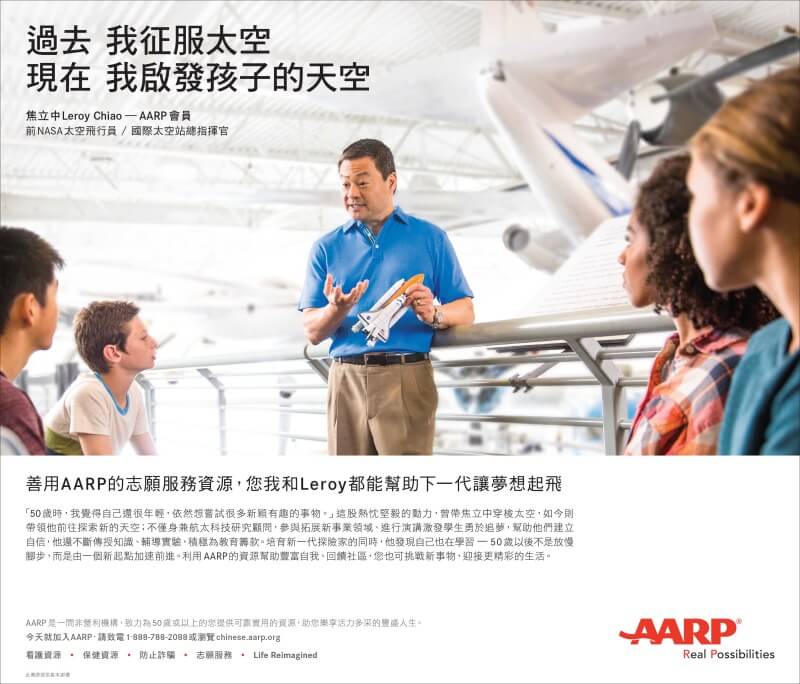

That lack of role models didn’t stop Leroy Chiao, who is one of only a handful of Asian Americans who have flown in space as a NASA astronaut. He flew on three Space Shuttle flights and was Commander of the Expedition 10 crew and lived on the International Space Station.

Chiao grew up in the Baby Boomer era when Asians weren’t generally included in mainstream American culture (except as the Chinese cook in “Bonanza,” the POW houseboy in “McHale’s Navy” and Kato, the martial arts-fighting chauffeur in “Green Hornet”). So he didn’t really think he was being ignored with the lack of role models.

He didn’t need an Asian role model to find his calling: after he watched Neil Armstrong make his historic moonwalk, young Chiao was hooked.

“When we landed on the moon in 1969, I was 8 years old. I was building model airplanes and model rockets even before we landed. When we landed, I thought ‘wow, that’s where I want to be.’ That’s where it started in my mind.”

Chiao lived in the San Francisco area, but not in a typical Chinese community. “My parents made a very conscious decision, when I was 7, to live in a mainstream area, so we were the only Asian family, basically, in the East Bay area,” he recalls. “Once I got to middle school and high school, I started hearing the racist stuff. I was always the smallest kid. Not only was I the smallest, I was youngest and smallest. It was a really rough time, being bullied and beat up.”

Even though he wasn’t living around a community of Chinese, his parents made sure he was raised with traditional Asian values.

“I had to do well in school, of course, but I wasn’t fully conscious of it. I knew I had to go to university, and I had to stay healthy just to be considered an astronaut. For me it was motivation to do well and make that happen,” he says.

Luckily, his interests in school fit with his goal of becoming an astronaut. “It was natural for me to study engineering because I liked technical things,” he says.

He studied the space program closely to wait for his chance. “I was very conscious of it,” he says. And he knew when to apply. “In 1978 NASA had just selected its first group of shuttle astronauts. For the first time they selected non-military people.”

He had tried to follow a path to NASA in college. “When I was a sophomore at Berkeley, I was in ROTC — I wanted to be fighter pilot.”

But his eyesight didn’t pass the 20/20 requirement. Then, when NASA looked outside the military, he pounced. “I was encouraged because they were taking civilians into the astronaut program.”

He was called several months after submitting his application.

“I was thrilled beyond belief,” he says with excitement in his voice even today. “It was what I was hoping for. It was exciting enough to apply and get called for an interview. I put my application in February of 1989. In the summertime I got a call from NASA asking if it would be OK to contact my employer. I thought ‘oh, that’s interesting.’ In September I got a call to come down to Houston for a week to be interviewed. I knew that I needed to not be the classic Asian stereotype. I needed to make points and tell them what I’d done. I knew this is my shot.”

A week later the FBI called Chiao and started a background investigation, and four months after he interviewed in Houston, at the age of 29, he was invited to join the shuttle astronaut program. “I found out later there were more than 2500 applications, and in my group they interviewed 23,” he says.

Chiao thinks he knows one reason there have been so few AAPI astronauts:

“I think the reason is that not that many apply. My advice to kids is: Have a dream, make a plan and have the courage to go after it. All my friends, we all wanted to be astronauts, but I was the only one that went after it.”

He says he’d tell young Asian Americans today who wonder, from watching Hollywood movies, if there’s a place for them in the stars, to go for it. In fact go for it whatever their passion is.

“I emphasize look at me, I tell them my story but what’s your story? If you’re interested in space that’s great but if you’re interested in art, business, dream big, go for it. Have a goal.

“I tell them look, I was not one of those kids who got good grades. Getting my undergraduate degree at Berkeley was one of the hardest things I’ve done in my life. I didn’t graduate 4.0 – I graduated 3.2.”

It helped that when he had the chance to submit his application, his parents supported his dream… at least, to a point. “They said that’s nice, go ahead and apply. They didn’t think I’d get in. When I got in they were happy, so go do this thing you’ve been excited about. I expected you to do great, so fine. But after a couple of years, come back to a respectable job like being an engineer.”

He says it never really occurred to him that Sulu on “Star Trek” was the only Asian character in space during his childhood. But he realizes now that Gene Roddenberry, the creator of the original TV series, was breaking new ground – going “where no man has gone before,” so to speak.

“I noticed they had the Asian character Sulu, but also black women, alien characters The creators of that show went to the trouble to do that. Even the concept of the half-breed alien. I didn’t think much of it at the time, but when I look back at it, I think wow, they were really out there.”

By the time the “Star Wars” franchise began in the late 1970s, Chiao was on track for space. “ I was almost 17 when the first one (“Star Wars Episode IV”) came out. It was really great. It certainly is a sci-fi movie but it was an action movie that took place in space.

Because he was a budding astronaut, Chiao says, “I noticed the glaring technical problems.” But he’s been a Star Wars fan nonetheless.

Chiao enjoys sci-fi films – his all-time favorite is the 1968 classic “2001: A Space Odyssey.” “I saw the Martian, and it was good. They made it more dramatic at the end than they had to.”

And, he noticed the casting. “Look at ‘The Martian.’ You don’t really see Asians.”

At least in the real world instead of Hollywood, Chiao is trying to change that. He wants to empower the next generation of Asian American kids to grow up knowing they can be astronauts.

“I have a presentation geared towards that – Asian American kids,” he says. “I talk about that experience. I vowed to be better than every one of those (bullies). There’s messaging about standing up for yourself.”

He started a company, One Orbit, that’s not necessarily geared toward Asian kids, but “overcoming fear of STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Math), fear of math, overcoming bullying,” he says.

He wants to see Asian Americans in leadership positions – and in space. In Hollywood too. He wants AAPIs to shout about themselves and reach for the stars.

“I grew up in a dual-culture world. It’s very Asian to not blow your own horn. Instead, it’s been work hard, keep your head down. That doesn’t work in Western culture. You do have to promote yourself. Otherwise they won’t know.”