I started my writing career as a music critic and became a journalist with jobs at various mainstream media newspapers and later, websites, and wasn’t much concerned with covering the Japanese, Japanese American or Asian American Pacific Islander communities or issues.

I started my writing career as a music critic and became a journalist with jobs at various mainstream media newspapers and later, websites, and wasn’t much concerned with covering the Japanese, Japanese American or Asian American Pacific Islander communities or issues.

I became curious about my roots when my father was diagnosed with lung cancer in the early ‘90s, but it wasn’t until a few years later before I started writing about being Japanese American. I met my wife, who is Sansei, in the late ‘90s and one of the first things she said to me was that I’m a “banana” – yellow on the outside, white on the inside.

She was right, even though I was actually born in Japan.

My dad was a Nisei born in Hawaii but my grandfather took the whole family back to Japan in 1940 and my dad and his siblings were stuck there during WWII. That’s a book that’s been stewing in the back of my head for a long time.

He stayed in Japan and became a houseboy at 13 for the US soldiers stationed there during the US Occupation. When he was old enough, he enlisted in the Army and he began getting a carton of Lucky Strikes every week as part of his GI rations. That was his ticket to lung cancer, I’m afraid – he smoked until his death.

My mom was born and raised in the small fishing town of Nemuro, on the easternmost tip of the northernmost island, Hokkaido. My dad was stationed there during the Korean War, and that’s where they met.

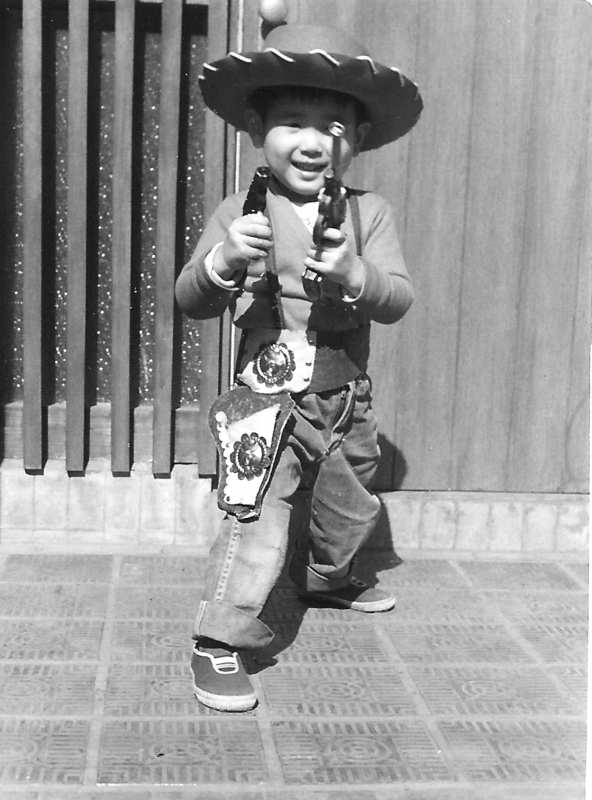

My early childhood was very bicultural – my family lived in Tokyo (and for a year, Iwakuni, near Hiroshima) neighborhoods and my brother and I took the bus to American schools on US military bases. It never occurred to me that I was living a split personality as Japanese and American. One year for Halloween I dressed as a cowboy, complete with western pistols on my hip; the next I dressed as a samurai. I played ninja with my Japanese friends and had crushes on white girls at school.

But when I was eight years old and my family moved to the states where my dad got a transfer to Washington, DC, it took me just a few weeks to become all-American. I learned every English cuss word, for one thing, even though I didn’t know what most of them meant. And, I forgot most of my Japanese (I never learned to read and write hiragana or katakana, even though my mom the equivalent of “Dick and Jane” language primers with us to America).

Tokyo, circa 1960

This was the background I had inside me when I went off to art school in New York City.

There, I was faced with noticing my identity for the first time – as an artist. I was approached by a Japanese sculptor to join a group of Japanese artists. I was part of the group for a while and participated in a gallery show in SoHo (true story: the playwright Edward Albee bought one of my paintings!), but I dropped out because I felt a bit uncomfortable, since I couldn’t speak Japanese and most of the others could.

Fast forward to after college, when I became a writer instead of an artist, and pursued a career in journalism. I never thought about covering “my” community, though. I wrote about rock music, folk music, country music, blues… never Japanese music (even though I grew up with and loved Japanese folksongs and enka). I was, well, a banana.

When my dad got sick from his lifetime of smoking Lucky Strikes, it suddenly dawned on me to ask what it was like to be at Pearl Harbor when it was bombed in 1941. “I don’t know,” he replied. “We moved to Japan the year before.”

That blew my mind. After he died in 1991, I interviewed his sisters about their life in Japan, and began researching the US Occupation of Japan, which ran from 1945-1952, the start of the Korean War. I later wrote about a trip to Japan to search for my family roots.

I became more interested in my Japanese side. By the late 1990s, I was writing a weekly column for Denver’s Japanese community newspaper, just thoughts on my childhood and flashes of Japanese culture in my life.

Through my wife, I was introduced to the community, and became a “born again JA.”

Because my weekly newspaper columns were a volunteer project and I owned my content, I began putting them on a simple website once I embraced the Internet. And when blogging came around, I converted my online columns to this blog, nikkeiview.com. Over the years I’ve expanded to write a lot about Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) issues of identity, culture and racism (an especially important topic today). But I try to keep things from my personal perspective and experience, and write with a conversational voice, something I developed over the years as a rock critic.

My blog led to my book, “Being Japanese American” (Stone Bridge Press, second edition 2014). The publisher specializes in books about Japan and was looking for a Japanese American book idea. They found my Nikkei View blog and asked me to write the book. Way back in 1991, I co-authored a fun book about toys of the baby-boom generation (“The Toy Book,” Alfred Knopf), but this was different. Being JA is a mix of personal stories and research, as well as the voices of other Nikkei (including some Japanese Canadians) with short anecdotes in the margins.

It was originally published in 2004, and Stone Bridge published an updated version in 2014. It’s been a blast because it establishes me as a legitimate voice for AAPIs. It‘s also a great calling card for meeting Nikkei everywhere. I’ve done book readings from New York to San Francisco, and even in Tokyo, to an audience that included three former Japanese ambassadors to the US!

I’m lucky. I didn’t have to struggle to come up with an idea and struggle to pitch the idea to an agent, or to a publisher. The book came to me. But I had spent a career setting the foundations for it, by becoming a writer, honing my skills, embracing the Internet early and establishing a reputation as a digital media pioneer, launching a blog, and promoting myself on social media.

Now, I put a lot of effort into doing the things that I can write about: being part of the local JA and AAPI communities, covering AAPI issues for clients including AARP and the Go For Broke National Education Center, participating in organizations including JACL, Japan America Society, US-Japan Council and Asian American Journalists Association.

I’ll always have plenty of material to share on social media and write about in my blog, and hopefully, more books in the future!

(Note: This essay was written for Nikkei Voice, the Canadian Japanese National Newspaper.)