Note: I’m now a regular monthly columnist for Discover Nikkei, the multilingual project of the Japanese American National Museum. For years they’ve repurposed my blog posts, but now the tables will be turned: I’ll write something for DN first, then post them afterwards here. This is the first column I wrote for them.

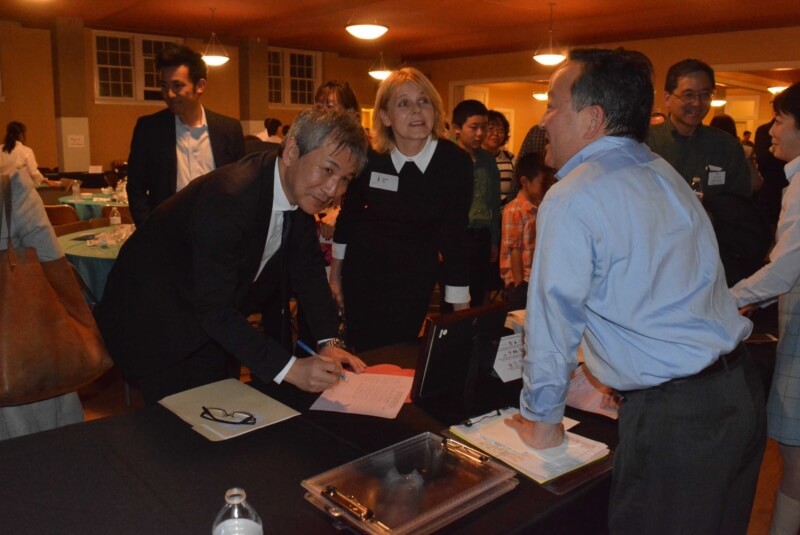

Consul General of Japan at Denver Makoto Ito and his wife Grace make a donation to continuing Tohoku relief efforts. Derek Okubo (right), the Executive Director of Denver’s Agency for Human Rights and Community Partnerships manned the donations table.

I can still remember March 11, 2011, the night of the Great East Japan Earthquake and subsequent tsunami, which devastated a huge swath of northeast Japan, as if it were last week.

It was just before midnight in Denver when I got an alert on my phone. An earthquake had been reported off the eastern coast of Japan. I turned on CNN and watched in horror for the next couple of hours as the footage came in. I saw the tsunami rolling over farmlands and crash into cities, carrying with it buildings and cars and ships. I saw footage of people trapped on rooftops. I saw houses being shoved aside as if they were origami boxes being blown by the wind, before they burst into flames. That was just the beginning; the seven meltdowns at the Fukushima Dai-Ichi nuclear plant were caused by the quake, and the cleanup around that disaster is still ongoing.

The disaster remains the worst earthquake in Japan’s recorded history, and the fourth worst in the recorded history of the world’s earthquakes. The toll was awful: almost 16,000 people have been confirmed dead, and over 2,500 still missing. Almost 229,000 people have been relocated or are still living in temporary housing.

Continue reading