Click to NikkeiView.com to visit the NEW Nikkei View blog!

THANKS!

The recent 72nd anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima went by quietly on American news (in part because there’s just so much news to cover exploding out of our own White House). So on Aug. 6 I turned to the one place I knew would give the commemoration of the bombing its due coverage: NHK World, Japan’s English-language public television network.

NHK World didn’t disappoint. The network aired live the annual solemn ceremony at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park that included dignitaries including Kazumi Matsui, the Mayor of Hiroshima, and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. The speeches were translated into English, and the dolorous seriousness of looking back at the horror of atomic war and looking with hope to a future without war were that much more powerful to be able to watch it live.

Sure, there are other ways to keep up with news from Japan. I have a digital subscription to JapanTimes.com , the website of the respected English-language newspaper. An aggregator called JapanToday.com compiles news from various sites and is a helpful stop to catch up on the headlines at a glance. The Asahi Shimbun’s English-language website (asahi.com/ajw) is also good.

But NHK has been the bridge to Japan for a lot of people in the US.

My mom watches the Japanese language programming via satellite exclusively, which means she never even tunes in another channel, even though she pays for a full service and the extra to get NHK. If she home, the TV is on, blasting do-rah-ma (dramas, or soap operas), wacky game shows, talk show, music and comedy variety shows, sumo tournaments and even children’s programming. The network also broadcasts news, of course, with its low-key and understated anchors (the game show hosts, on the other hand seem as if they’ve just downed a gallon of cold-brew coffee before the cameras turned on).

My mom loves the samurai doramas and pastoral nature shows, but gets puzzled watching the news. I’ve visited her when the news is on and she has no idea what many contemporary words that Japanese use mean. Having come to America in the mid-sixties, she never learned more modern terms like “pasocon” (personal computers) or “poppu musicu” (pop music). Even though I have limited Nihongo ability, I can pick out the “katakana words,” as she calls them, and end up telling her what the report is about. Katakana is the alphabet that’s used for foreign words.

For years whenever I traveled to other cities, I’d check the hotel television menu to see if they carried NHK World, the English version of the network my mom watches.

Continue reading

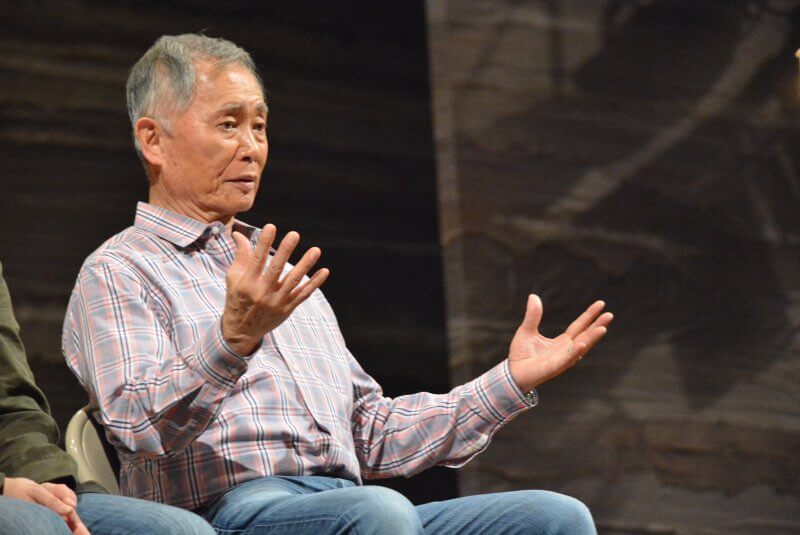

George Takei speaking to the audience at a Talkback session following a performance of “Allegiance” in New York in November, 2015.

Like many people, and especially many Japanese Americans, I’m a big fan of George Takei. I’ve followed his career since I first saw him in the role of Lieutenant Hikaru Sulu in the original 1960s television “Star Trek” series and as he reprised the character in subsequent Star Trek movies in the 1970s and 1980s.

Instead of fading into pop culture history after the Star Trek movies, he’s reinvented himself in both politics and pop culture, and today he’s hands-down the best-known and influential Asian American and an activist for human rights. He’s truly the Energizer Bunny of AAPI role models.

The Japanese American National Museum in LA has honored Takei with an exhibit, “New Frontiers: The Many Worlds of George Takei” that closes August 20. Takei is a member of the museum’s Board of Trustees, and is a vocal supporter of the institution. JANM returns the favor with this overview of Takei’s epic career, from acting to activism, and his current status as a social media superstar. I wish I lived I LA so I could see the exhibition!

Continue reading

The historical story of the Japanese American incarceration during World War II is still not well-known in mainstream American culture and literature. When it comes to books, there are only a handful of books that are based on JAs’ wartime experience. After the groundbreaking, angry “No-No Boy” by John Okada in 1957, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s “Farewell to Manazanar” was the first well-known memoir in 1973 (and made better-knwon because of its 1976 TV movie adaptation). The 1994 novel “Snow Falling on Cedars” is the most famailiar to non-JA audiences (again, because of the 1999 Oscar-nominated Hollywood film version).

The historical story of the Japanese American incarceration during World War II is still not well-known in mainstream American culture and literature. When it comes to books, there are only a handful of books that are based on JAs’ wartime experience. After the groundbreaking, angry “No-No Boy” by John Okada in 1957, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s “Farewell to Manazanar” was the first well-known memoir in 1973 (and made better-knwon because of its 1976 TV movie adaptation). The 1994 novel “Snow Falling on Cedars” is the most famailiar to non-JA audiences (again, because of the 1999 Oscar-nominated Hollywood film version).

“Why She Left Us” by Rahna Reiko Rizzuto in 1999 delved into the emotional distress of incarceration. I loved “The Red Kimono,” a 2013 novel by Jan Morrill that told the story of life in a concentration camp in Arkansas from the perspective of a young girl.

Now, we can add to this short list of excellent literature, “The Little Exile” by Jeanette Arakawa, a first-time author who couches her own story in a fictionalized novel instead of a memoir.

The fictional framing serves the story well, and gives Arakawa the creative freedom of shaping the narrative and dialogue for a sweeping, epic look at her family’s history that starts in pre-war San Francisco and ends as her family returns to the Bay Area after the war, and after spending time in Denver upon leaving the Rohwer concentration camp in Arkansas. Yet, that history is told in exquisite vignettes, as if she is remembering one memory at a time, turning them over like a Rubik’s Cube in her mind and then lining up the colors before moving on to the next memory.

Continue reading

I started my writing career as a music critic and became a journalist with jobs at various mainstream media newspapers and later, websites, and wasn’t much concerned with covering the Japanese, Japanese American or Asian American Pacific Islander communities or issues.

I started my writing career as a music critic and became a journalist with jobs at various mainstream media newspapers and later, websites, and wasn’t much concerned with covering the Japanese, Japanese American or Asian American Pacific Islander communities or issues.

I became curious about my roots when my father was diagnosed with lung cancer in the early ‘90s, but it wasn’t until a few years later before I started writing about being Japanese American. I met my wife, who is Sansei, in the late ‘90s and one of the first things she said to me was that I’m a “banana” – yellow on the outside, white on the inside.

She was right, even though I was actually born in Japan.

My dad was a Nisei born in Hawaii but my grandfather took the whole family back to Japan in 1940 and my dad and his siblings were stuck there during WWII. That’s a book that’s been stewing in the back of my head for a long time.

He stayed in Japan and became a houseboy at 13 for the US soldiers stationed there during the US Occupation. When he was old enough, he enlisted in the Army and he began getting a carton of Lucky Strikes every week as part of his GI rations. That was his ticket to lung cancer, I’m afraid – he smoked until his death.

My mom was born and raised in the small fishing town of Nemuro, on the easternmost tip of the northernmost island, Hokkaido. My dad was stationed there during the Korean War, and that’s where they met.

My early childhood was very bicultural – my family lived in Tokyo (and for a year, Iwakuni, near Hiroshima) neighborhoods and my brother and I took the bus to American schools on US military bases. It never occurred to me that I was living a split personality as Japanese and American. One year for Halloween I dressed as a cowboy, complete with western pistols on my hip; the next I dressed as a samurai. I played ninja with my Japanese friends and had crushes on white girls at school.

But when I was eight years old and my family moved to the states where my dad got a transfer to Washington, DC, it took me just a few weeks to become all-American. I learned every English cuss word, for one thing, even though I didn’t know what most of them meant. And, I forgot most of my Japanese (I never learned to read and write hiragana or katakana, even though my mom the equivalent of “Dick and Jane” language primers with us to America).

Continue reading